CT Families Continue to Struggle Financially, United Way Report Reveals

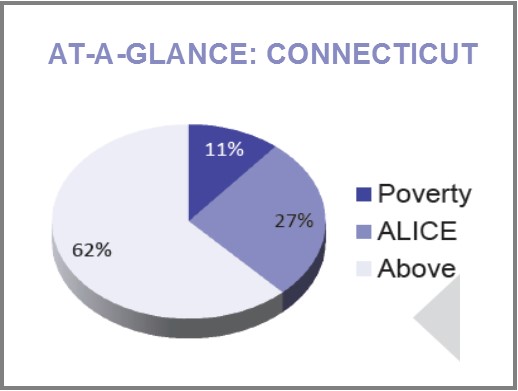

/More Connecticut households are struggling to pay for their most basic needs, according to a new report from United Way. More than one out of four households - in one of the wealthiest states in the U.S. - are employed, yet still fall below what is needed to thrive financially. That is an increase in both the number and percentage of such households in 2014 as compared with 2012, according to the updated ALICE report.

Two years ago, United Ways introduced ALICE, which stands for - Asset Limited Income Constrained Employed - to place a spotlight on a large population of residents who are working, but have difficulty affording the basic necessities of housing, food, child care, health care and transportation.

In those two years, the problem has grown worse, even has the recession has given way to a slow economic recovery, in Connecticut and nationwide. ALICE and poverty households combined account for 38 percent of households in the state that struggle to make ends meet.

A total of 361,521 Connecticut households fall into what the study describes as the ALICE population. These are households earning more than the official U.S. poverty level, but less than the basic cost of living. This is more than 2.5 times the number of households that fall below the federal poverty level. ALICE households make up 20% or more of all households in 114 (67%) of Connecticut’s 169 cities and towns.

The highest levels (ALICE and poverty households) were in Hartford (74%), New Haven (65%), Waterbury (63%), Bridgeport (63%) and New Britain (63%). Also above 50 percent are Meriden, West Haven, East Hartford and New London. From 2007 to 2014, two cities, Danbury and Waterbury, saw their total household population decrease, by 7 and 9 percent respectively, while the rest experienced an increase in households, with the largest increase of 8 percent in Stamford, according to the report. The number of household below the ALICE Threshold increased in every one of the nine largest cities and towns with Norwalk seeing the largest percent increase (38 percent).

While the prevalence of low-wage jobs still defines Connecticut’s economy for ALICE, for the first time in the past decade, the percent of jobs paying less than $20 per hour fell below 50 percent of all jobs. The report also highlights a number of trends in Connecticut, including:

While the prevalence of low-wage jobs still defines Connecticut’s economy for ALICE, for the first time in the past decade, the percent of jobs paying less than $20 per hour fell below 50 percent of all jobs. The report also highlights a number of trends in Connecticut, including:

- The population is aging, and many seniors do not have the resources they need to support themselves.

- Differences by race and ethnicity persist and ethnicity persist, creating challenges for many ALICE families, as well as for immigrants in Connecticut.

- Low-wage jobs are projected to grow faster than higher-wage jobs over the next decade.

- Technology is changing the workplace, adding some jobs, replacing many others, while also changing where people work, the hours they work, and skills required. The report notes that technology creates opportunities as well as challenges for ALICE workers.

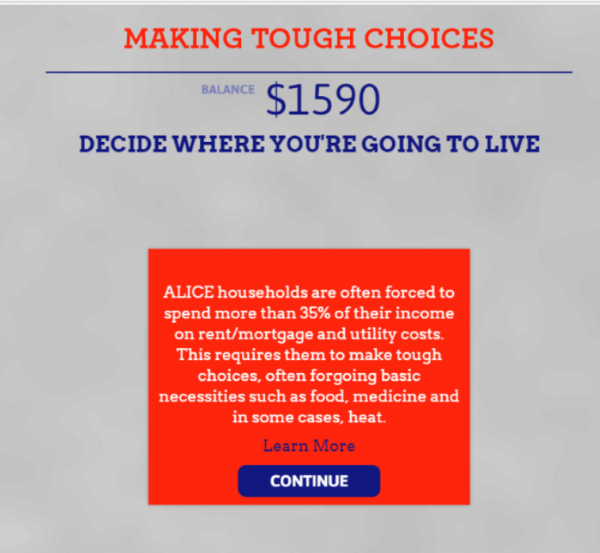

For the first time, an online simulator is also available to experience the financial challenges that ALICE households in Connecticut face at www.MakingToughChoices.org. The updated Report uses data from a variety of sources, including the U.S. Census and the American Community Survey to provide tools that quantify the number of households in Connecticut's workforce that are struggling financially. The updated United Way ALICE Report reveals:

- The composition of the ALICE population is men and women, young and old, of all races.

- The breakdown of jobs in Connecticut by hourly wage (51% of jobs pay more than $20/hour) compared to what it costs to survive for a family of four (2 adults, 1 infant, 1 preschooler) - $70,788.

- Every city and town in Connecticut has ALICE households. More than two-thirds of Connecticut's cities and towns have at least 1 in 5 households that fit the ALICE definition for financial hardship.

Poverty and ALICE households exist in every racial and ethnic group in Connecticut, but the largest numbers are among White non-Hispanic households. There were about one million White households in 2014, compared to 328,000 households of color (Figure 4 shows the populations of color for whom there is income data: Hispanic, Black and Asian). However, these groups made up a proportionally larger share of households both in poverty and ALICE: 64 percent of Hispanic households, 58 percent of Black households, and 30 percent of Asian households had income below the ALICE Threshold in 2014, compared to 31 percent of White households.

The largest population of color in Connecticut, Hispanics, has been growing since 2007, totaling 156,837 households in 2014, a 25 percent increase. As the number of Hispanic households increased, so did the number and proportion of Hispanics living below the ALICE threshold. The percentage of Hispanic ALICE households rose from 34 percent in 2007 to 39 percent in 2010 and then to 43 percent in 2014. Together Hispanic households in poverty and ALICE made up more than two-thirds of Hispanic households in 2014.

There are some signs of improvement in the education gap among racial and ethnic groups, suggesting that some structural changes are occurring in Connecticut. In K-12 education, the Education Equality Index (EEI) shows that the achievement gap – the disparity in educational measures between socioeconomic and racial or ethnic groups – narrowed slightly between 2011 and 2014 in Connecticut.

There are some signs of improvement in the education gap among racial and ethnic groups, suggesting that some structural changes are occurring in Connecticut. In K-12 education, the Education Equality Index (EEI) shows that the achievement gap – the disparity in educational measures between socioeconomic and racial or ethnic groups – narrowed slightly between 2011 and 2014 in Connecticut.

Achievement gaps impact graduation rates and college performance. Among the Class of 2013, 64 percent of Black students and 59 percent of Hispanic students in the state went on to college within a year after graduating from high school, compared to 78 percent of White students. They also had lower 6-year college graduation rates: While 54 percent of White students got a college degree within 6 years, only 24 percent of Black students and 21 percent of Hispanic students did the same (Connecticut State Department of Education, 2015).

The updated ALICE Report recommends both short-term and long-term strategies to help ALICE families and strengthen our communities. United Ways work with many community partners to provide support to ALICE families to help them get through a crisis and avoid a downward spiral into even worse circumstances such as homelessness as well as assisting with financial literacy, education and workforce readiness.

Further, United Ways in Connecticut have invested more than $8.5 million in child care and early learning; $1.3 million in housing and homeless prevention work; $5 million in basic needs programs; and, have assisted working families in obtaining nearly $40 million in EITC and tax refunds and credits in 2016.

The updated Connecticut ALICE Report was funded by the 16 Connecticut United Ways. For more information or to find data about ALICE in local communities, visit http://alice.ctunitedway.org. Connecticut United Ways are joining with United Ways in fifteen other states to provide statewide ALICE Reports. The updated Connecticut ALICE Report provides analysis of how many households are struggling in every town, and what it costs to pay for basic necessities in different parts of the state (Household Survival Budget).

https://youtu.be/u7gPJGu2psw

[2014 ALICE introductory video]

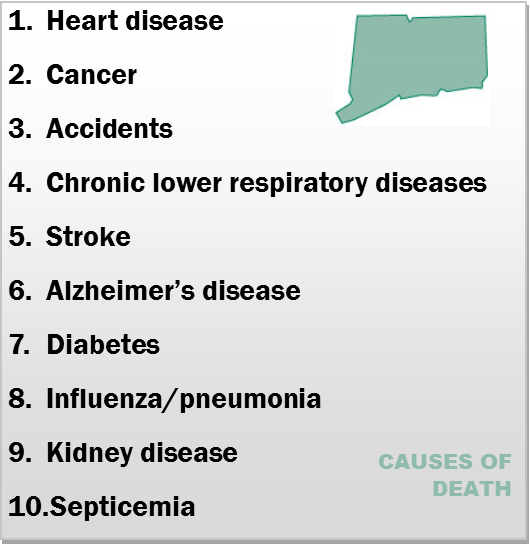

eaths due to diabetes, and 48th in deaths caused by stroke. The state ranked 15th, however, in deaths caused by septicemia and 35th in accidental deaths.

eaths due to diabetes, and 48th in deaths caused by stroke. The state ranked 15th, however, in deaths caused by septicemia and 35th in accidental deaths.

At #296 is Glastonbury-based Fiondella Milone & LaSaracina. FML was founded in 2002 “for the purpose of providing professional auditing, tax and business consulting services to a wide range of clients and industries throughout the Northeast,” the company’s website indicates. After working together at Ernst & Young, the firm’s founding partners, Jeff Fiondella, Frank Milone and Lisa LaSaracina launched FML.

At #296 is Glastonbury-based Fiondella Milone & LaSaracina. FML was founded in 2002 “for the purpose of providing professional auditing, tax and business consulting services to a wide range of clients and industries throughout the Northeast,” the company’s website indicates. After working together at Ernst & Young, the firm’s founding partners, Jeff Fiondella, Frank Milone and Lisa LaSaracina launched FML. counting newsletter and the award-winning National Benchmarking Report.

counting newsletter and the award-winning National Benchmarking Report. In addition to the expert panel on opioid abuse, there will be more than 30 presenters on public health topics, a presentation on the history of CPHA and public health in the

In addition to the expert panel on opioid abuse, there will be more than 30 presenters on public health topics, a presentation on the history of CPHA and public health in the state, and a look forward to the future and innovations on the horizon in health research, policy, and community programs.

state, and a look forward to the future and innovations on the horizon in health research, policy, and community programs. She seeks to broaden the national health debate to include not only universal access to high quality health care but also attention to the social determinants of health (including poverty) and the social determinants of equity (including racism). As a methodologist, she has developed new ways for comparing full distributions of data (rather than means or proportions) in order to investigate population-level risk factors and propose population-level interventions.

She seeks to broaden the national health debate to include not only universal access to high quality health care but also attention to the social determinants of health (including poverty) and the social determinants of equity (including racism). As a methodologist, she has developed new ways for comparing full distributions of data (rather than means or proportions) in order to investigate population-level risk factors and propose population-level interventions.

e: Financing Women’s Growth-Oriented Firms (published by Stanford University Press), which points to “three essential factors that women entrepreneurs need to thrive: knowledge, networks, and investors. In tandem, these three ingredients connect and empower emerging entrepreneurs with those who have succeeded in growing their firms while also realizing the financial and economic returns that come with doing so.”

e: Financing Women’s Growth-Oriented Firms (published by Stanford University Press), which points to “three essential factors that women entrepreneurs need to thrive: knowledge, networks, and investors. In tandem, these three ingredients connect and empower emerging entrepreneurs with those who have succeeded in growing their firms while also realizing the financial and economic returns that come with doing so.”

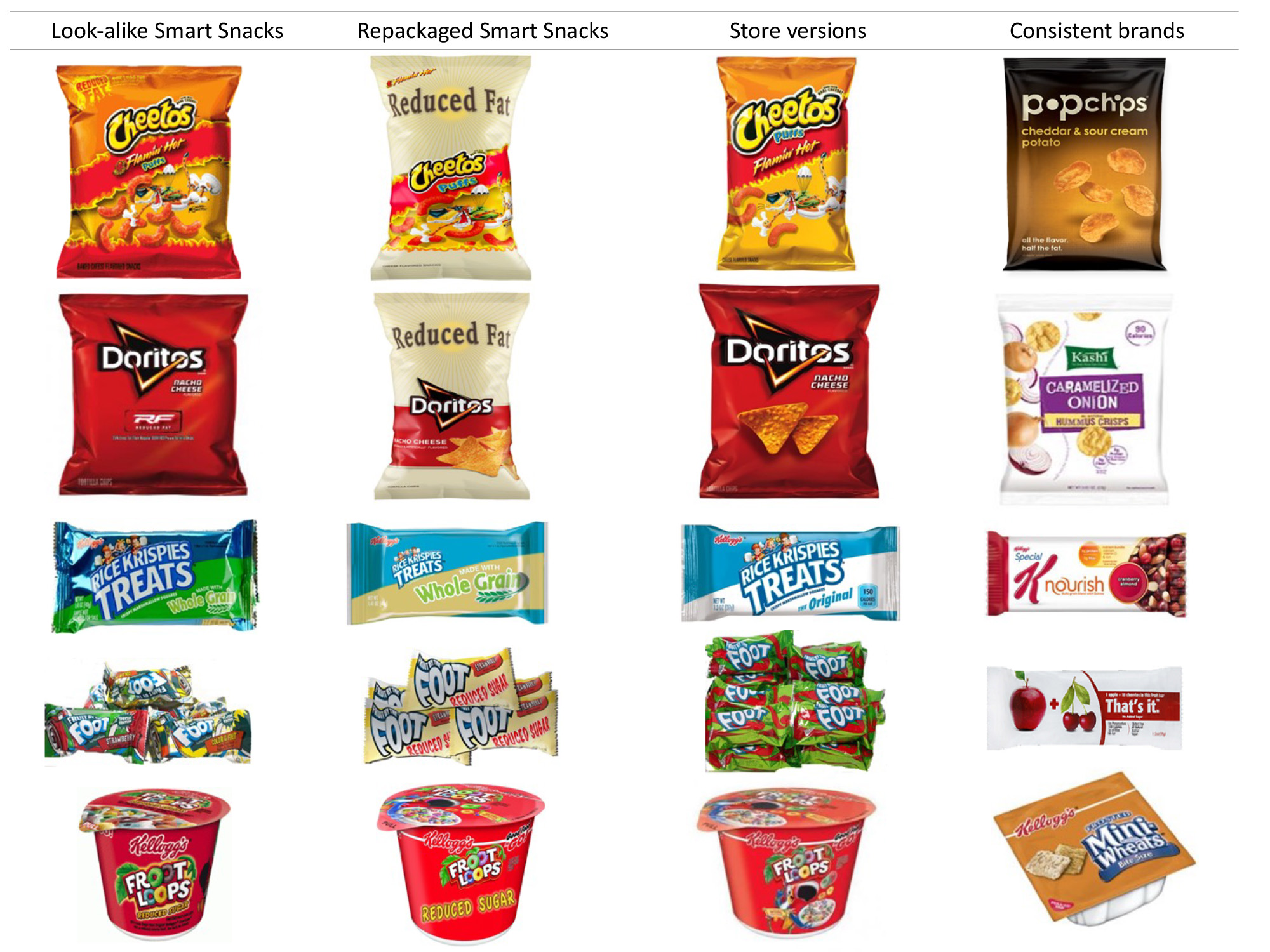

“The practice of selling look-alike Smart Snacks in schools likely benefits the brands,” says Harris, “but may not improve children’s overall diet, and undermines schools’ ability to teach and model good nutrition.”

“The practice of selling look-alike Smart Snacks in schools likely benefits the brands,” says Harris, “but may not improve children’s overall diet, and undermines schools’ ability to teach and model good nutrition.”

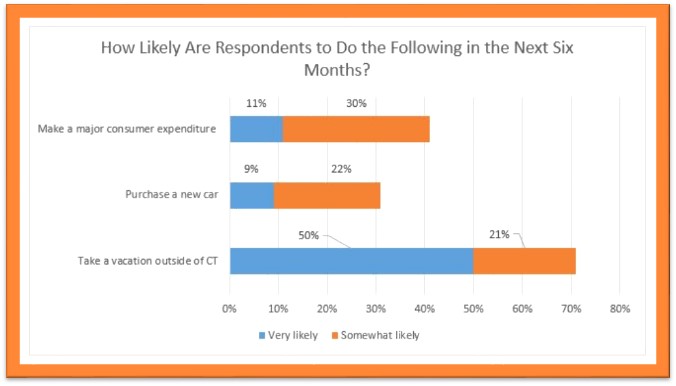

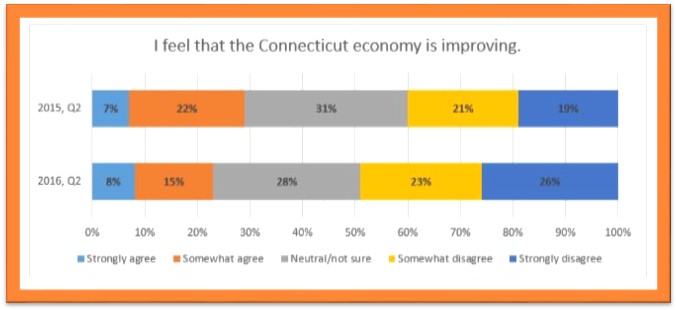

Increasingly, residents believe that jobs are “very hard to get” in Connecticut compared with six months ago (from about one-quarter to one-third of those surveyed in Q2 2016 versus Q2 2015), and are, in growing numbers, saying they would rather leave than stay.

Increasingly, residents believe that jobs are “very hard to get” in Connecticut compared with six months ago (from about one-quarter to one-third of those surveyed in Q2 2016 versus Q2 2015), and are, in growing numbers, saying they would rather leave than stay. Forty-three percent, an increase from 40 percent in the year’s first quarter, answered “all of the above” when asked if education, libraries, public health, public safety and animal control could be provided regionally. Among those services individually, there was slightly greater support for a regional approach to public safety, slightly less for each of the others. The largest increase was for “all” of the services.

Forty-three percent, an increase from 40 percent in the year’s first quarter, answered “all of the above” when asked if education, libraries, public health, public safety and animal control could be provided regionally. Among those services individually, there was slightly greater support for a regional approach to public safety, slightly less for each of the others. The largest increase was for “all” of the services.

The

The  A minimum-wage worker in Connecticut would need to work full time for 36 weeks, or from January to September, just to pay for child care for one infant. And a typical child care worker in Connecticut would have to spend 63.6% of her earnings to put her own child in infant care, according to the data.

A minimum-wage worker in Connecticut would need to work full time for 36 weeks, or from January to September, just to pay for child care for one infant. And a typical child care worker in Connecticut would have to spend 63.6% of her earnings to put her own child in infant care, according to the data.