PERSPECTIVE: Highway Winter Maintenance Pay off? Safety!

/by Eric Jackson, PhD and Donald Larsen, PE

In Connecticut, as in many other snow belt states, the state Department of Transportation (CTDOT) as well as local Public Works Departments (DPWs) can suddenly be thrust into the spotlight (or the hot seat) when winter storms hit, particularly when driving conditions deteriorate. Our daily exposure to lightning fast activities and information, which allow us to assess situations a nd form opinions rapidly have altered our expectations.

nd form opinions rapidly have altered our expectations.

Interestingly, as little as ten years ago, when a winter storm would make travel hazardous and place our busy lives on hold, we seemed able to adapt, maybe wait a day, adjust and move on. Today’s society has little patience for travel delays and the “privilege” to travel is now seen as more of a right.

Fortunately, the CTDOT does not view this challenge as insurmountable and has used foresight and innovation to keep winter travel as safe as possible. Since the winter sea son of 2006/2007 CTDOT has changed the way winter maintenance is performed. They have discontinued the use of abrasives (such as sand) and phased in methods known as ‘anti-icing’ strategies [1]. These strategies have been honed and polished continually over the past ten years.

son of 2006/2007 CTDOT has changed the way winter maintenance is performed. They have discontinued the use of abrasives (such as sand) and phased in methods known as ‘anti-icing’ strategies [1]. These strategies have been honed and polished continually over the past ten years.

The Connecticut Academy of Science and Engineering (CASE) prepared a report for the Connecticut General Assembly in 2015 that evaluated winter maintenance strategies employed at CTDOT. This study reviewed CTDOT’s anti-icing effects on safety, the environment, and corrosion of vehicles and highway infrastructure. The entire report can be found at http://www.ctcase.org/reports/ [2]. The safety implications of these changes were analyzed using the Connecticut Crash Data Repository (CTCDR), a motor vehicle crash database housed at the University of Connecticut.

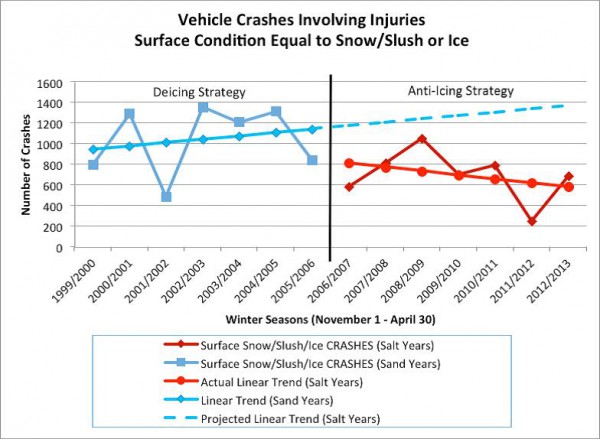

An analysis of vehicle crashes over thirteen winter seasons, 1999 to 2013, was conducted to try and evaluate the impact of anti-icing on safety (see chart). A comparison of crashes, specifically for state-maintained roads during winter seasons, indicates that injuries declined by 19.2%, on average, since anti-icing strategies were implemented. When crashes on snow/slush or ice surface conditions were examined the average reduction in crashes with nonfatal injuries was an even more dramatic, 33.5%.

CHART: Motor vehicle crashes involving nonfatal injuries with pavement surface condition equal to snow/slush or ice on Connecticut state-maintained roadways.

The reduction in the number of motor vehicle crashes with nonfatal injuries is a significant finding because according to a study by Qiu et al at the University of Iowa the rate of crashes on snow can be 84% higher than on dry pavement [3]. With an estimated cost in 2010 (from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration) of $276,000 per non-incapacitating injury, [4] society- including everyone that travels - benefits from this significant reduction in injurious crashes.

Between 2006 and 2013, there was a reduction of 2,449 crashes with nonfatal injuries on Connecticut state-maintained roadways during snow/slush or ice conditions. This calculates out to a cost savings of approximately $676 million.*

Other ongoing research throughout the world shows that plowing is still the most cost effective way to clear the roadways of snow and ice. Abrasives such as sand, grit or stone dust do not remove the snow or ice, and only delay the inevitable need for removal or melting.

However, the anti-icing techniques – the scientific application of deicing chemicals such as salt and other materials - provide a very important aid to snow/ice removal operations, preventing ice and snow from bonding to paved surfaces. With anti-icing, the time period with snow covered roads – which are those critical times when crashes are most likely to occur - is also reduced.

From the estimated savings shown, it is important that CTDOT and the local municipal DPWs continue to improve winter maintenance by employing state-of-the-art equipment for chemical applications, timely snow and ice removal, and using weather monitoring stations as well as advanced weather prediction services and models. It appears that from the safety benefits alone, the continued expenditures made on winter maintenance have paid off. Reducing the negative economic impact that results when people and goods don’t move is another benefit.

The CTCDR is available to anyone wishing to view motor vehicle crash statistics in Connecticut, for any type of crash, under any road conditions. Connecticut is one of the few states that maintains a publicly accessible crash database. It is highly recommended that if you have an interest in crash data, visit http://ctcrash.uconn.edu/ [5].

____________________________________

Dr. Eric Jackson is an Associate Research Professor in the School of Engineering at the University of Connecticut and is Director of the Connecticut Transportation Safety Research Center. Donald Larsen PE, is a Temporary University Specialist at the Connecticut Transportation Institute at UConn and former Supervising Engineer with the Connecticut Department of Transportation

PERSPECTIVE commentaries by contributing writers appear each Sunday on Connecticut by the Numbers.

LAST WEEK: Do Community College Students Go Begging?

______________

[1] CTDOT Staff, An Overview of Snow and Ice Control Operations on State Highways in Connecticut, Office of Maintenance, Bureau of Highway Operations, Connecticut Department of Transportation, Newington, CT, June 2015.

[2] Mahoney, J., D. Larsen, E. Jackson, K. Wille, T. Vadas, and S. Zinke, Winter Highway Maintenance Operations: Connecticut, Publication CT-2289-F-15-1, CTDOT, Connecticut Academy of Science and Engineering, July 2015. http://www.ctcase.org/reports/WinterHighway2015/winter-highway-2015.pdf

[3] Qiu, L., and W. Nixon, Effects of Adverse Weather on Traffic Crashes, Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, No. 2055, Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, Washington, D.C., 2008, pp. 139-146.

[4] Blincoe, L. J., Miller, T. R., Zaloshnja, E., & Lawrence, B. A., The Economic and Societal Impact of Motor Vehicle Crashes, 2010, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, USDOT, Washington, DC, Report No. DOT HS 812 013, May 2014, (rev. 2015, May).

[5] Connecticut Crash Data Repository, Connecticut Transportation Institute, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT. Website. http://ctcrash.uconn.edu/ (Accessed May 5, 2016).

* For purposes of this calculation, each crash was arbitrarily assigned one non-incapacitating injury.

This article is based on a study conducted by the Connecticut Academy of Science and Engineering on behalf of the Connecticut Department of Transportation. Eric Jackson and Donald Larsen served as members of the Research Team from the Connecticut Transportation Institute at the University of Connecticut. Access the full study report, an executive summary, and briefing at http://www.ctcase.org/reports/index.html