Former UConn QB Cochran Says Football Puts Players in Harm’s Way, Urges End to "Cycle of Silence"

/Former UConn quarterback Casey Cochran, who retired from the sport at age 20 after suffering his 13th concussion, said this week that “There are problems with the game that need to be addressed. As it is played right now, tackle football — with its pads and helmets — puts players in harm’s way, all of the time, regardless of age and ability.” Cochran, writing a first-person story about his experiences with football and concussions in The Players’ Tribune, an online site founded by Derek Jeter, issued an alert to others who’ve journeyed through the sport, or continue to compete:

“I want to say to all former, current and future athletes who have or will suffer a concussion: Do not hide it. Tell your coaches, medical staff, parents, friends and teammates. Get treatment. The cycle of silence hurts more and more people each year.”

Cochran, from Monroe, explained that in the 18 months since his decision, after suffering a concussion on the last play of the first game of UConn’s 2014 season, against Brigham Young University, “I still feel the lingering effects from my many concussions. Life is a balancing act now. Some days it’s hard to wake up before noon. Sometimes I don’t want to leave my bed at all. In high school, I had a 3.9 GPA. Now I have trouble focusing and performing well in my graduate-school classes.”

He warned that “Those who play football, particularly those who begin in their youth, are given a glamorized version of the sport – one where camaraderie, discipline, toughness and leadership are highlighted and the wretchedness is ignored and swept under the rug. As a result, we fall in love with and value the good and push aside the bad.”

Cochran recalled that “I probably should have stopped playing football in eighth grade after my third concussion, but I was afraid to speak up. Afraid of disappointing people who had invested in my career. Afraid of who was I was without football. I wish I hadn’t hid the three concussions I had in one week during my junior year of high school, but I was afraid that college recruiters would find out.”

Even with increasing awareness of the risks of concussions, Cochran said the near and long-term effects haven’t led to enough changes. “The only word I know to describe the first few moments after a concussion is limbo — there are a few moments between the world that you were just a part of and your new brain-injured reality,” Cochran explained. “My head was seized with tremendous pressure, and that same awful, familiar depression from previous head injuries came over me — like a dark, heavy blanket, swallowing me up.”

With it all, he retains optimism: “There is life outside of the white lines. A lot of life. Stepping away from football was one of the scariest things I’ve ever had to do. I felt lost for a long time. For a little over a year, I felt like I was somewhere, deep in the ocean, being pulled by the currents. But what pulled me back from the depths was hope. Hope that things would get better.”

He now finds purpose in being an advocate for player safety, speaking to audiences, doing interviews and writing a book about his experiences. To those going through what he did, during his 14 years of playing football, he says “If you feel alone, you aren’t. Chances are, there are a lot of people out there who have some idea of what you’re going through. Just keep looking. Reach out.”

Added Cochran: “Sometimes it’s nice to admit that things aren’t O.K.: ‘Hello, my name is Casey, and I have anxiety and depression.’ It may be permanent. It may be just the beginning. I don’t know what the future has in store for me and it will be some time before the medical field can paint a clearer picture for me. I may have CTE right now. I might have dementia at 50. My entire future is uncertain.”

Des Moines Golf and Country Club was the site of the 1999 U.S. Senior Open Championship which drew a record 252,800 spectators.

Des Moines Golf and Country Club was the site of the 1999 U.S. Senior Open Championship which drew a record 252,800 spectators.

Why does USA Gymnastics keep coming back? “Everything runs smoothly,” suggests Mikulak, expressing a competitor’s viewpoint. “They trust us,” adds Murdock, noting that when Connecticut bids to attract future national caliber sporting events, the first question asked is “what else have you hosted.”

Why does USA Gymnastics keep coming back? “Everything runs smoothly,” suggests Mikulak, expressing a competitor’s viewpoint. “They trust us,” adds Murdock, noting that when Connecticut bids to attract future national caliber sporting events, the first question asked is “what else have you hosted.”

The three-day event

The three-day event  r 39 U.S. titles and 12 world championships medals. 2012 Olympian and three-time U.S. champion Sam Mikulak of Newport Coast, Calif., is pursuing his fourth consecutive U.S. all-around title. Including Mikulak, four members of the 2012 U.S. Men’s Olympic Team are slated to compete in Hartford this weekend.

r 39 U.S. titles and 12 world championships medals. 2012 Olympian and three-time U.S. champion Sam Mikulak of Newport Coast, Calif., is pursuing his fourth consecutive U.S. all-around title. Including Mikulak, four members of the 2012 U.S. Men’s Olympic Team are slated to compete in Hartford this weekend. cut will be back in the sports spotlight later this summer, with the

cut will be back in the sports spotlight later this summer, with the  Just weeks later, New Haven will be hosting the

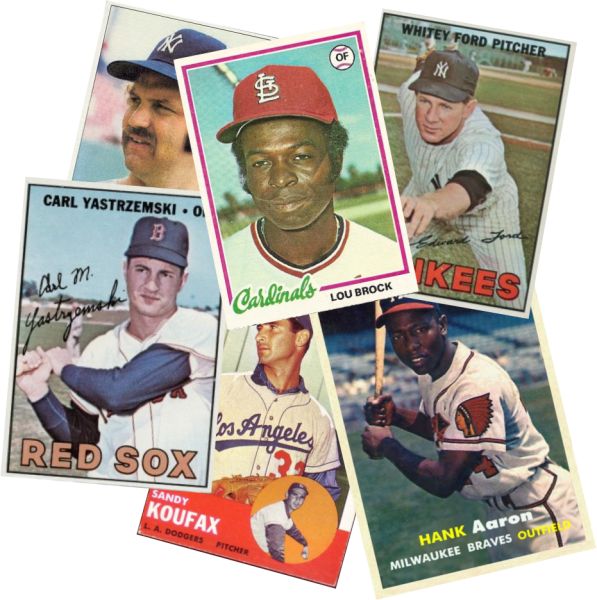

Just weeks later, New Haven will be hosting the  impact of a seller’s race in a field experiment involving baseball card auctions on eBay. The results, according to the researchers, left little doubt.

impact of a seller’s race in a field experiment involving baseball card auctions on eBay. The results, according to the researchers, left little doubt.

e first total was larger.”

e first total was larger.” e Gordon Bradford Tweedy Professor at Yale Law School and the Director of the Law and Economics Program at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) with headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

e Gordon Bradford Tweedy Professor at Yale Law School and the Director of the Law and Economics Program at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) with headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Stamford has a public park named in his honor, recalling that Robinson represented tolerance, educational opportunity, and the confidence that inspires personal achievement and success. A life-size bronze statue of Jackie Robinson with an engraved base bearing the words “COURAGE,” “CONFIDENCE,” AND “PERSEVERANCE” stands in the park located on West Main Street, the gateway to downtown Stamford.

Stamford has a public park named in his honor, recalling that Robinson represented tolerance, educational opportunity, and the confidence that inspires personal achievement and success. A life-size bronze statue of Jackie Robinson with an engraved base bearing the words “COURAGE,” “CONFIDENCE,” AND “PERSEVERANCE” stands in the park located on West Main Street, the gateway to downtown Stamford. “It brought back very personal memories of my father talking about his trip to Cuba in 1947, when the Brooklyn Dodgers trained in Havana. At the time, dad was a member of the Dodgers' farm team, the Montreal Royals. Branch Rickey arranged for him to fly to Cuba for an exhibition game, just a couple of months before he broke down baseball's color barrier in the United States. To me, this connection to my father almost brought me to tears. I was watching a baseball game in the same stadium nearly 70 years later.”

“It brought back very personal memories of my father talking about his trip to Cuba in 1947, when the Brooklyn Dodgers trained in Havana. At the time, dad was a member of the Dodgers' farm team, the Montreal Royals. Branch Rickey arranged for him to fly to Cuba for an exhibition game, just a couple of months before he broke down baseball's color barrier in the United States. To me, this connection to my father almost brought me to tears. I was watching a baseball game in the same stadium nearly 70 years later.”

ast season as the New Britain Rock Cats, the team

ast season as the New Britain Rock Cats, the team

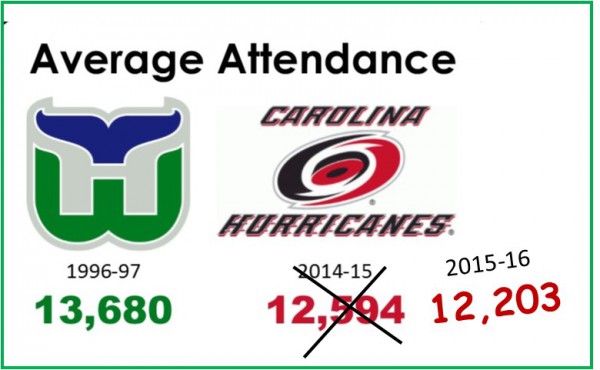

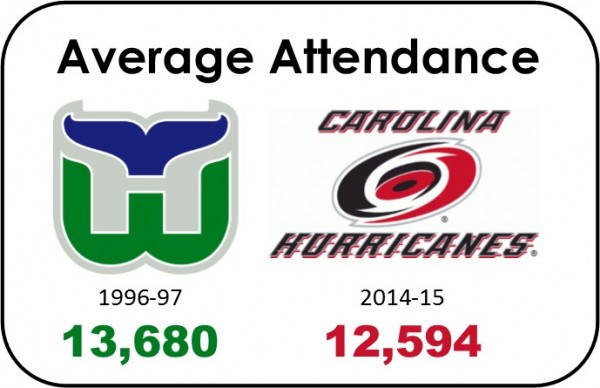

ave the Whale” season-ticket drive resulted in 8,300 season tickets sold, about 3,000 more than the previous year. In the aftermath of the season ticket drive, and heading into the 1996-97 season, the Whalers management said they would remain in Hartford for two more years, in accordance with their lease.

ave the Whale” season-ticket drive resulted in 8,300 season tickets sold, about 3,000 more than the previous year. In the aftermath of the season ticket drive, and heading into the 1996-97 season, the Whalers management said they would remain in Hartford for two more years, in accordance with their lease. efore management moved the team from Hartford. (To 10,407 in 1993-94, 11,835 in 1994-95, 11,983 in 1995-96 and 13,680 in 1996-97.)

efore management moved the team from Hartford. (To 10,407 in 1993-94, 11,835 in 1994-95, 11,983 in 1995-96 and 13,680 in 1996-97.)