Disparities Continue As Uneven Economic Recovery Challenges Children and Families; Changes Urged

/Connecticut lost 85,358 jobs during the recession, which technically ended nearly seven years ago. The state has continued to hemorrhage manufacturing jobs, however, and industries dependable before the crash—particularly those in finance and health care—grew more slowly or not at all. According to a new report by Connecticut Voices for Children, 97.7 percent of Connecticut’s net job losses were in mid- or high-wage industries and 51 percent of the job losses occurred in the manufacturing and construction sectors, with another 15 percent of job losses occurring in retail trade.

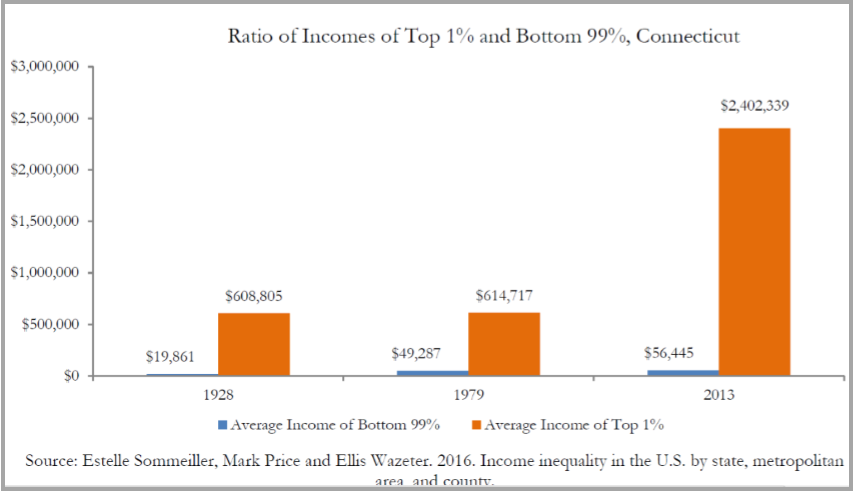

The financial disparity in the state’s population is more stark than ever, the report said. “Over the past thirty years, incomes for the bottom 99 percent grew by just 14.5 percent, while the incomes of the top 1 percent swelled by 290.8 percent. As a result of this lopsided growth—a period in which the top 1 percent captured 71.6 percent of all income—incomes of the top 1 percent are now 42.6 times greater than the bottom 99 percent.”

The report stresses that many Connecticut working families have been left out of the economic recovery. “As the share of low-wage jobs rises, so does the challenge of raising a family,” the report states. “The jobs created in low-wage sectors not only pay less, but often provide less flexibility, less predictability and fewer benefits than jobs past.”

In the report. Connecticut Voices for Children points out that the combination of an increase in the share of low-wage jobs, slow wage growth and persistently high unemployment for minorities and workers without a college education threaten the long term well-being of the state. Data highlighted points out that “black and Hispanic workers in Connecticut make median hourly wages that are, respectively, $7.25 and $8 less than white workers’—a gap that has widened since before the Great Recession.”

Among the recommendations: raise the minimum wage. Raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour would offer relief to 336,000 workers, the report points out, which would help those the state's recovery has left farthest behind. Breaking down the demographics, the research report indicated that 60 percent of benefitting workers would be women; 31.8 percent of all black workers and 37.5 percent of all Hispanic workers would benefit.

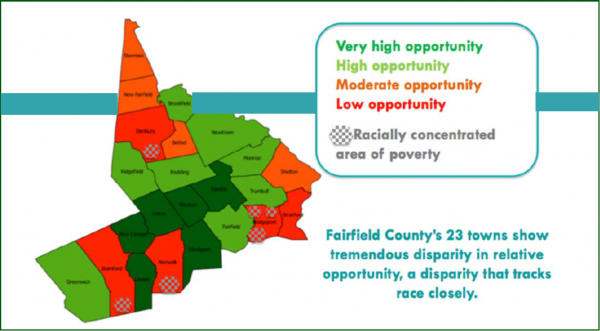

“Changes in the state economy pose challenges for low wage workers seeking to give their children the best possible start in life,” says Ellen Shemitz, Executive Director of Connecticut Voices for Children. “Higher unemployment and lower wages for workers of color exacerbate existing disparities in opportunity, with significant implications for both the competitiveness and fairness of our state’s economy.”

The report documents a long term shift in job and wage trends in Connecticut, with almost half of all jobs created since the start of the recovery in low-wage industries. Since 2001, the share of industries that typically pay low-wages has increased by 20 percent, while high-wage industry employment has decreased by 13 percent.

The report documents a long term shift in job and wage trends in Connecticut, with almost half of all jobs created since the start of the recovery in low-wage industries. Since 2001, the share of industries that typically pay low-wages has increased by 20 percent, while high-wage industry employment has decreased by 13 percent.

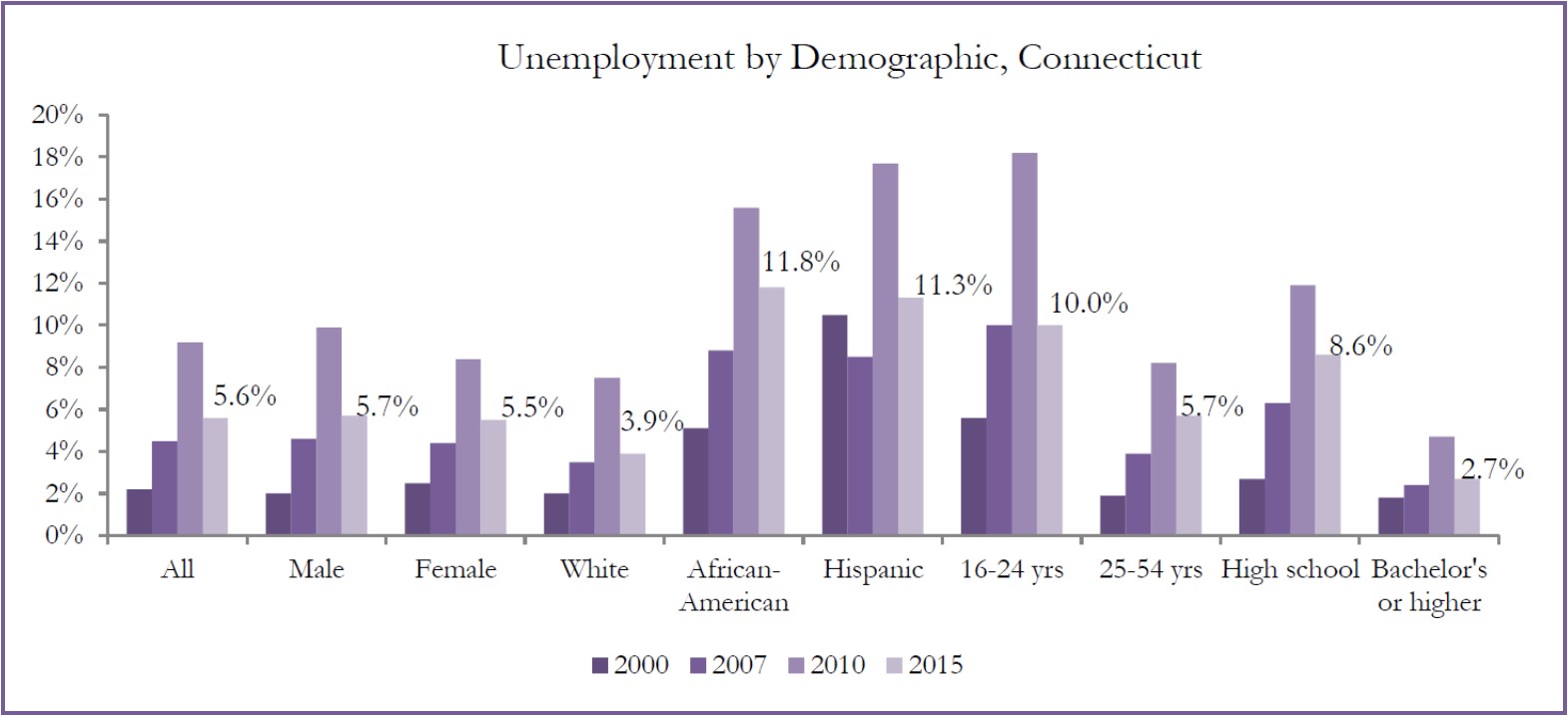

At the same time, unemployment has returned to pre-recession levels for white and college educated workers, but unemployment for workers of color and those without a college education have yet to recover. Despite years of sustained job growth, these workers face unemployment rates that are three times higher than whites.

“Connecticut’s jobs swap has implications for individual family economic well-being and for the state’s overall revenue sufficiency,” explained Derek Thomas, Fiscal Policy Fellow at Connecticut Voices for Children and report co-author. “The first decade in the 21st-century – which includes the loss of manufacturing jobs in the early 2000s as well as the vast job losses during the Great Recession – has left the state with a sizeable high-wage jobs deficit.”

Among the reports’ key findings:

- Since 2010, unemployment has steadily declined for white and college educated workers, but not for workers of color and those without a college education. Unemployment for workers of color is nearly triple than for whites.

- Underemployment remains stubbornly high; the rate of part-time employees that would want to work full-time and workers that have given up on their job search in the past year is two times higher today that it was in 2007.

- Since 2001, the share of private-sector jobs in low-wage industries has increased by 20 percent, while the share of private-sector jobs in high-wage industries has decreased by 13 percent. Nearly half of new private sector jobs since 2010 are in low-wage industries.

- The median and bottom 10 percent of wage-earners have seen their wages decline by more than 2 percent since 2002, while the top 10 percent have experienced growth of more than 11 percent.

- Black workers’ median hourly wage is $8 lower than white workers and Hispanic workers’ median hourly wage is $7.25 lower than white workers.

Since the workplace is meeting fewer of the needs of children and families, Connecticut Voices for Children is urging state policy makers to take action to bridge the gap between wages and the growing cost of raising a family. The report recommends five key policy initiatives:

Since the workplace is meeting fewer of the needs of children and families, Connecticut Voices for Children is urging state policy makers to take action to bridge the gap between wages and the growing cost of raising a family. The report recommends five key policy initiatives:

- Restore the earned income tax credit for low income workers to its original 2011 levels, allowing low wage workers to retain more of what they have earned

- Raise the minimum wage to $15, allowing low wage workers to cover their families’ basic needs

- Expand high-quality early childhood education to remove barriers to employment for parents and better prepare future generations of workers

- Strengthen infrastructure investments to ensure economic competitiveness and economy-boosting jobs

- Reform property taxes for a more equitable education system

Because workers of color are overrepresented in the low-wage industries that have driven the state’s job recovery, racial and ethnic wage gaps have widened. “The growth in low-wage industries is a double whammy for working families – not only do they pay less, but they also lack the benefits, predictability and flexibility of jobs past,” says Ray Noonan, Associate Fiscal Policy Fellow at Connecticut Voices for Children and report co-author.

Connecticut Voices for Children is a research-based policy think tank based in New Haven. The organization’s mission is to promote the well-being of all of Connecticut's young people and their families by advocating for strategic public investments and wise public policies. To achieve these objectives, Connecticut Voices for Children produces “high quality research and analysis, promotes citizen education, advocates for policy change at the state and local level and works to develop the next generation of leaders.”

Connecticut Voices for Children is a research-based think tank that focuses on issues that affect child well-being, from educational opportunity to healthy child development to family economic security. Its mission is to ensure that all of Connecticut’s children have the opportunity to achieve their full potential.

Connecticut Voices for Children is a research-based think tank that focuses on issues that affect child well-being, from educational opportunity to healthy child development to family economic security. Its mission is to ensure that all of Connecticut’s children have the opportunity to achieve their full potential.