by Alissa DeJonge

A combination of factors are having a negative impact on state revenues, contributing to budget woes. The different age cohorts in Connecticut’s population tell an important story of one reason revenues are declining. State legislators need to examine Connecticut’s current and future demographics as they look to solve fiscal problems.

Much of the daily news centers on the state budget deficit and the lengths that legislators are attempting to go to find ways to balance it. There is a projected $220 million shortfall for this fiscal year that was addressed by legislators on March 29.[1] And the projected shortfall for the next fiscal year is approaching $1 billion.

Legislators are quite aware that revenues are not coming in to the extent originally anticipated, and that this trend has been occurring for the past number of years. Indeed, Senator Beth Bye, during a March 23 conference about broadband infrastructure,[2] discussed the revenue woes and the dire situation that Connecticut is facing.

What makes this situation particularly serious is the fact that the reasons there is a ‘revenue problem’ have been long in the making, and the trend is poised to continue.

Of course, the overall state economy continues to struggle. Connecticut is one of 10 U.S. states that has not regained all the jobs lost since the last recession.[3] If jobs are sluggish, so too are revenues back to the state. And wage growth, while seeing improvements in 2015, has been relatively flat since the end of the last recession, which also keeps state revenues in a static to declining state.[4]

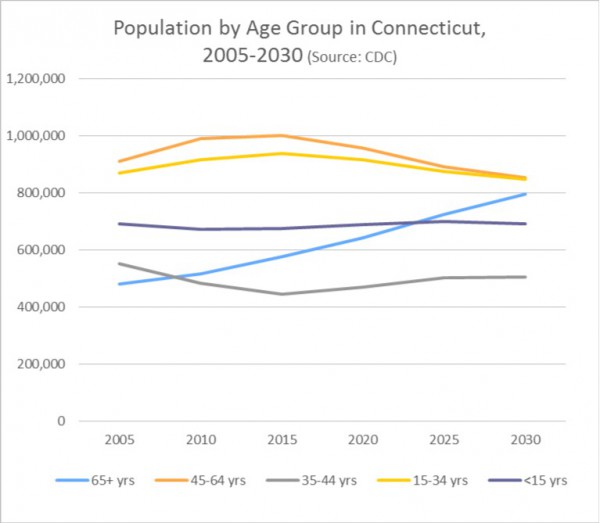

However, the lack of revenues also involves overall demographic patterns. The figure shows population by age for Connecticut between 2005 and 2015, and projections extending to 2030.

- The age group over 65 is projected to increase 38% between 2015 and 2030. This will add much pressure to state services such as Medicaid and long term supports and services while at the same

time reducing revenues because this large age cohort is no longer working.

time reducing revenues because this large age cohort is no longer working.

- The Baby Boomer generation, those who are currently 45-64 years old, comprise the largest share of the state’s population. As they move from employment to retirement, the trend of increasing service needs and lessening revenues will accelerate.

- Generation Xers will fill many Boomer jobs, but they are a much smaller group, which means that state revenues are unlikely to regain their previous higher levels because fewer people will be producing outputs.

- The current Millennials (roughly ages 15-34 years) and the even younger Generation Z population have more people in their age groups then the Generation Xers. Therefore, demographic trends should eventually contribute to increasing state revenues. But it will be well over a decade before the Millennials begin to gain seniority and higher wages in the workforce and contribute more to the state revenues.

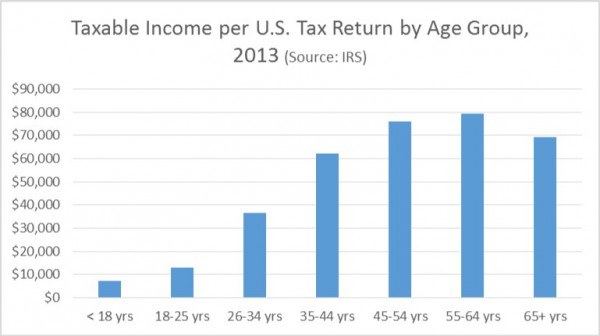

This figure shows how taxable income ebbs and flows by age group. The Baby Boomers are in the best position to contribute to state revenues right now. However they are retiring in a consistent fashion, and the next younger cohort, of which there are fewer people to begin with, is earning less than their mature counterparts. This sets up a long-term issue for state revenue potential, one that will not be mitigated until the larger Millennial age cohort gets into their more profitable working years.

This figure shows how taxable income ebbs and flows by age group. The Baby Boomers are in the best position to contribute to state revenues right now. However they are retiring in a consistent fashion, and the next younger cohort, of which there are fewer people to begin with, is earning less than their mature counterparts. This sets up a long-term issue for state revenue potential, one that will not be mitigated until the larger Millennial age cohort gets into their more profitable working years.

Revenue expectations are not what they used to be. In the 1960s, the economy consistently grew between three and five percent each year, and Americans assumed that it would continue to grow at that pace. As a result, government was able to fund additional programs as economic and tax bases kept expanding. Today the economy is growing at only around two percent each year. This economic trend reduces the ability for the government to fund programs, and all demands cannot be met, with the current revenues coming in.[5]

If you multiply the taxable income per return by the number of people in each demographic group in both 2015 and 2030, excluding inflation, there would be a four percent decrease in the projected total amount of taxable income in the state. This illustrates the effect of demographic trends on taxable income. Without even considering job trends, wage trends, or other long-term economic factors, the demographic shifts of the population are going to make it even more challenging for state governments to raise revenues.

The state revenue problem will not resolve itself with this legislative session, or even the next. While the current revenue problems are a combination of many factors, the demographic influence is significant and should not be overlooked because it can provide insight for decades into the future.

Since there are a number of longer term, structural issues that will continue to affect the state’s ability to raise revenues for many years, stakeholders and policymakers will have to adjust to this new economic reality. Prioritization of programs with specific intended targeted outcomes is the approach to the state budgeting process needed now.

_________________________________

Alissa DeJonge is Vice President of Research, Connecticut Economic Resource Center Inc. (CERC).

PERSPECTIVE commentaries by contributing writers appear each Sunday on Connecticut by the Numbers.

LAST WEEK: Freedom's Just Another Word For...

_________________________________

[1] http://www.nbcconnecticut.com/news/local/Vote-on-State-Budget-Deficit-Expected-Tuesday-373779281.html (Accessed March 29, 2016)

[2] High-Speed Broadband Internet Infrastructure Informational Conference: A Toolbox for Municipalities (March 23, 2016)

[3] http://www.usnews.com/news/business/articles/2016-03-25/job-totals-trail-pre-recession-levels-in-10-us-states (Accessed March 29, 2016), from U.S. DOL calculations of jobs changes, December 2007 – February 2016.

[4] http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2015/oct/8/comptroller-connecticut-wage-growth-continues-to-l/ (Accessed March 29, 2016)

[5] Robert Samuelson, Trump’s Wrong – We’re Hugely Well-Off (Op-Ed), The Hartford Courant, March 28, 2016.

time reducing revenues because this large age cohort is no longer working.

time reducing revenues because this large age cohort is no longer working. This figure shows how taxable income ebbs and flows by age group. The Baby Boomers are in the best position to contribute to state revenues right now. However they are retiring in a consistent fashion, and the next younger cohort, of which there are fewer people to begin with, is earning less than their mature counterparts. This sets up a long-term issue for state revenue potential, one that will not be mitigated until the larger Millennial age cohort gets into their more profitable working years.

This figure shows how taxable income ebbs and flows by age group. The Baby Boomers are in the best position to contribute to state revenues right now. However they are retiring in a consistent fashion, and the next younger cohort, of which there are fewer people to begin with, is earning less than their mature counterparts. This sets up a long-term issue for state revenue potential, one that will not be mitigated until the larger Millennial age cohort gets into their more profitable working years.

Alabama’s special session – the first in five years - was held over the summer, convening on July 13 and ending in disarray in mid-August, with a second special session on the state budget convened and concluded in mid-September. Among the

Alabama’s special session – the first in five years - was held over the summer, convening on July 13 and ending in disarray in mid-August, with a second special session on the state budget convened and concluded in mid-September. Among the

Democratic legislative leaders and Republican legislative leaders are

Democratic legislative leaders and Republican legislative leaders are