The collective response to America’s opioid crisis has opened a new front in Connecticut in an unlikely location – the public library. Driven by a desire to be prepared to save a life, a growing number of libraries – in communities large and small – now have the opioid reversal drug naloxone on hand, with librarians trained in how to use it.

Naloxone is a medication that can reverse and block the effects of other opioids. It can very quickly restore normal respiration to a person whose breathing has slowed or stopped as a result of overdosing with heroin or prescription opioid pain medications.

The U.S. Surgeon General has issued a nationwide public health advisory, to “urge more Americans to carry a potentially lifesaving medication that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose.” That office reports that an estimated 2.1 million people in the U.S. struggle with an opioid use disorder.

For Marlborough’s Richmond Memorial Library, the decision to train three staff members to administer the medication was wholly consistent with what a library is all about, as director Nancy Wood explains.

“I liken it to the defibrillator that we brought in to the library two years ago. If you are saving a life for one reason, you can save a life for another. And it is a cultural thing for librarians to want to help people. It is what we do.”

As a significant public place in Marlborough, open more hours than just about any other building in town, Wood says that although “hopefully we never have to use it,” she and her staff felt it was important to be trained and ready. The AHM Youth & Family Services organization provided the training last March.

Rates of opioid overdose deaths are rapidly increasing nationwide and in Connecticut. Since 2010, the number of opioid overdose deaths in the U.S. has doubled from more than 21,000 to more than 42,000 in 2016. Overdose deaths in Connecticut have nearly tripled in a six-year period, from 357 in 2012 to 1,038 in 2017. Of those 1,038 deaths, 677 involved fentanyl — a synthetic opioid drug 30 to 50 times more powerful than heroin — either by itself or with at least one other drug, according to published reports.

According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, between June 2017 and June 2018, there were 1,056 reported cases of drug overdose deaths, based on provisional data, in Connecticut. An analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation concluded that the opioid overdose death rate in Connecticut was the 10th highest in the nation, and the percentage increase between 2016 and 2017 was 17th highest in the U.S., exceeding the national average.

According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, between June 2017 and June 2018, there were 1,056 reported cases of drug overdose deaths, based on provisional data, in Connecticut. An analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation concluded that the opioid overdose death rate in Connecticut was the 10th highest in the nation, and the percentage increase between 2016 and 2017 was 17th highest in the U.S., exceeding the national average.

Hartford recently announced a $10,000 grant from CIGNA Foundation that will train librarians in the city and cover the purchase of naloxone for city libraries.

“As a public institution, we see that our entire community is impacted by the opioid crisis; it was clear that a rapid and robust response to the problems caused by the opioid drug crisis was imperative,” said library CEO Bridget Quinn-Carey as the grant was announced earlier this month. Library officials also plan to provide information about opioid abuse awareness and host education and information forums.

When the town of Canton made training available for department heads last year, library director Sarah McCusker took the one-day session. Like Wood, she views it as an extension of first aid training that can help a patron in distress.

“It’s the same as knowing CPR or having an AED on-site. We call 911 immediately, but we see everything, and we’d like to be prepared,” McCusker explained. She also believes employees in public spaces should be “widely trained” to assist in emergency situations. And she anticipates that if her town government makes training in the use of naloxone available again this year, although it is not mandated, additional staff members will choose to attend.

The Connecticut Library Consortium indicates that while official figures are not available, reports of libraries having naloxone available, along with official policies governing its use and trained staff members, are increasing. Hartford, Marlborough, Canton and Avon are among them. Other libraries have librarians on staff who have sought and received individual training. For many libraries, it is a major health issue that their municipalities and local governing boards are reviewing, and one that impacts cities and small towns.

The naloxone brand NARCAN® Nasal Spray is a pre-filled, needle-free device that requires no assembly and is sprayed into one nostril while patients lay on their back. Those prepared to administer it have been trained on the signs of an opioid overdoes, and how to respond immediately as 911 is called for a local ambulance response.

“Public libraries are responsible for meeting the wide-ranging needs of their communities. Yes, libraries offer books and storytime programs and research help that goes beyond Google. But they are also the place to turn to find a job, become a citizen, discover a new app, find quality healthcare information, make art, or learn a new skill,” said Jennifer Keohane, Executive Director of the Connecticut Library Consortium. “Having library staff who are trained to administer NARCAN is another way that libraries are evolving with their communities and are ready to provide help whenever and however it is needed.”

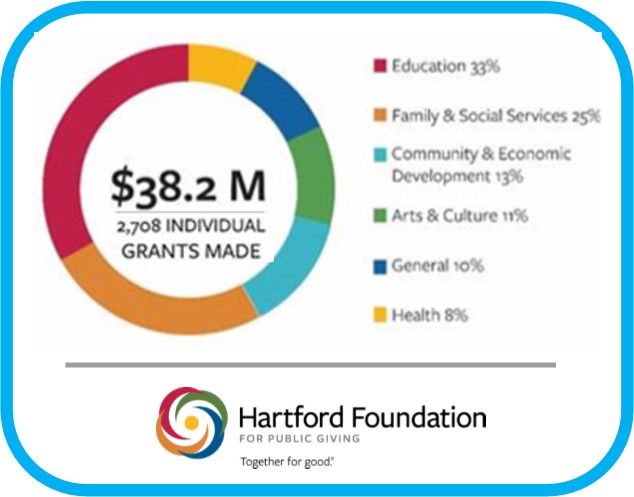

Among the grants, in each program area:

Among the grants, in each program area:

According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, between June 2017 and June 2018, there were 1,056 reported cases of drug overdose deaths, based on provisional data, in Connecticut. An

According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, between June 2017 and June 2018, there were 1,056 reported cases of drug overdose deaths, based on provisional data, in Connecticut. An