What would happen if ways to integrate nature into a major urban community were pursued? In Connecticut, the largest city is Bridgeport, and the Connecticut chapter of The Nature Conservancy (TNC) has been undertaking an effort to find out.

Nature offers a lot of benefits to communities, TNC points out. “Trees provide shade and help clean the air. Gardens absorb and filter water, which reduces flooding and runoff into nearby rivers. Healthy dunes and wetlands protect coastlines from storms.” In addition, the organization points out, “nature can also transform the way people experience their neighborhood.”

With 70 percent of the world’s population predicted to live in cities by 2050, heat and air pollution constitute a major public health concern, TNC points out, underscoring the importance of the organization’s initiatives to plant trees in urban areas across the country, among a series of related undertakings.

“People are at the core of our efforts to identify how neighborhoods are addressing daunting challenges in this formerly industrialized city,” said Drew Goldsman, Urban Conservation Program Manager. “We want to partner with communities to implement natural solutions in Bridgeport that help both people and nature.”

Their Eco-Urban Assessment looked at areas in Bridgeport that have poor air quality, high risk of flooding, and limited access to nearby green spaces and layered it with data on income level, impervious surfaces and asthma rates. The team was able to pinpoint neighborhoods where trees, green stormwater systems and open spaces will make the biggest difference for people and nature. Air quality and flood risk topped the list of most acute needs.

In collaboration with local partners, the Conservancy is supporting a neighborhood-led greening effort known as ‘Green Connections’ in Bridgeport’s East Side neighborhood. Creating a plan for ways natural resources can shape the future of the community while making immediate changes to the landscape —through tree plantings and green stormwater infrastructure projects— is one of the initiative’s main goals, along with empowering volunteer stewards living in the community to take ownership of these natural areas. All of this helps create safe spaces for the community to gather, provides cooler and cleaner air, and improves wildlife habitat in the city.

According to the Nature Conservancy, Bridgeport currently has a 19% tree canopy cover, for example. If all open spaces, vacant lots and parking lots could be planted, the city would have a 62% tree canopy cover. The ramifications would be substantial, impacting various health and quality of life factors.

According to the Nature Conservancy, Bridgeport currently has a 19% tree canopy cover, for example. If all open spaces, vacant lots and parking lots could be planted, the city would have a 62% tree canopy cover. The ramifications would be substantial, impacting various health and quality of life factors.

“Healthier people, cooler temperatures in the summer, cleaner air, reduced flooding, more urban habitat, parks and forests, less sewage overflow, a clean Pequannock River a more resilient coastline and green jobs” are cited as potential benefits.

The national publication Governing pointed out last year that “Streets cover about a third of the land in cities, and they account for half of the impervious surfaces in cities. Impervious surfaces don’t allow water to soak through them, which means they can alter the natural flow of rainwater. City streets collect, channel, pollute and sometimes even speed along water as it heads to the sewers.”

Goldsman indicates that currently efforts are focusing on the city of Bridgeport, but the Eco-Urban Assessment model is available to urban communities that want a deeper understanding of where nature can bring solutions to some of the most pressing urban issues.

“With the Eco-Urban Assessment model, we’re able to help municipalities identify the places and ways we can work together to use nature to improve residents’ quality of life and build more sustainable communities,” said Dr. Frogard Ryan, Connecticut state director for The Nature Conservancy. “From the beginning, we wanted this to be a community-led and TNC-supported program. Residents help us identify areas of other focus that aren’t highlighted by the model and be sure our study reflects what people experience day-to-day.”

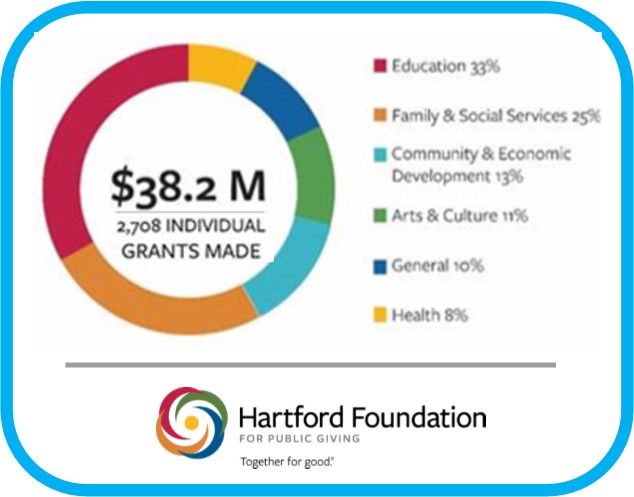

Among the grants, in each program area:

Among the grants, in each program area:

The just under-the-wire recipients:

The just under-the-wire recipients:

“Girl Scouts is one of our nation’s most powerful leadership training grounds for young women,” said Openshaw. “We’re thrilled to support Girl Scouts as it seeks to modernize and remain relevant for young women in the new global economy.”

“Girl Scouts is one of our nation’s most powerful leadership training grounds for young women,” said Openshaw. “We’re thrilled to support Girl Scouts as it seeks to modernize and remain relevant for young women in the new global economy.” The 40-page report, developed by The Child Health and Development Institute of Connecticut (CHDI), a subsidiary of the Children’s Fund of Connecticut, in partnership with the national Center for School Mental Health at the University of Maryland, provides a framework for policymakers and school districts interested in improving outcomes by addressing the mental health and trauma needs of students. The report indicates that “in a typical classroom of 25 students, approximately five will meet criteria for a mental health disorder but most of them are not receiving appropriate mental health treatment or support. Among those who do access care, approximately 70 percent receive services through their schools.”

The 40-page report, developed by The Child Health and Development Institute of Connecticut (CHDI), a subsidiary of the Children’s Fund of Connecticut, in partnership with the national Center for School Mental Health at the University of Maryland, provides a framework for policymakers and school districts interested in improving outcomes by addressing the mental health and trauma needs of students. The report indicates that “in a typical classroom of 25 students, approximately five will meet criteria for a mental health disorder but most of them are not receiving appropriate mental health treatment or support. Among those who do access care, approximately 70 percent receive services through their schools.” “Approaching student mental health with a comprehensive lens that integrates health promotion, prevention, early intervention, and more intensive treatments leads to better school, student and community outcomes," said Dr. Sharon Hoover, Co-Director of the Center for School Mental Health at the University of Maryland and lead author of the report.

“Approaching student mental health with a comprehensive lens that integrates health promotion, prevention, early intervention, and more intensive treatments leads to better school, student and community outcomes," said Dr. Sharon Hoover, Co-Director of the Center for School Mental Health at the University of Maryland and lead author of the report.

According to the Nature Conservancy, Bridgeport currently has a 19% tree canopy cover, for example. If all open spaces, vacant lots and parking lots could be planted, the city would have a 62% tree canopy cover. The ramifications would be substantial, impacting various health and quality of life factors.

According to the Nature Conservancy, Bridgeport currently has a 19% tree canopy cover, for example. If all open spaces, vacant lots and parking lots could be planted, the city would have a 62% tree canopy cover. The ramifications would be substantial, impacting various health and quality of life factors.

“This is an exciting opportunity for all of us at Foodshare. More produce and healthier options: that’s the future of food banking,” said Jason Jakubowski, President and CEO of Foodshare.

“This is an exciting opportunity for all of us at Foodshare. More produce and healthier options: that’s the future of food banking,” said Jason Jakubowski, President and CEO of Foodshare.