As the Connecticut legislature considers a proposal to implement a 2 percent tax on sodas, proposed by Senate Majority Leader Martin Looney at the suggestion of New Haven Mayor and former state senator Toni Harp, two new academic studies challenge the beverage industry’s view that state and local taxes on sugary drinks will hurt employment, and offer suggestions to policy makers based on the tobacco tax experience.

Harp has said the soda tax would discourage consumption of the sugary beverages – part of her campaign to combat obesity - and bring in  an estimated $144 million in revenue for the state each year. It would tax all beverages “high in calories or sugar” by two percent, but does not specify how many calories or grams of sugar would trigger the tax.

an estimated $144 million in revenue for the state each year. It would tax all beverages “high in calories or sugar” by two percent, but does not specify how many calories or grams of sugar would trigger the tax.

The studies, appearing in the February and March issues of the American Journal of Public Health, argue, in one case, that claims of employment losses are off base because they focus only on the effects within the industry, ignoring the economic activity that comes with people substituting lower-priced goods for more expensive products as well as new spending from tax revenues. The other study says that tobacco taxes offer a how-to road map for policy makers.

as new spending from tax revenues. The other study says that tobacco taxes offer a how-to road map for policy makers.

The study to be published in March, led by Jennifer L. Pomeranz, JD, MPH, while at the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity at Yale University, uses as its premise that “excise taxes on sugary beverages have been proposed as a method to replicate the public health success of tobacco control and to generate revenue.”

“Sugary Beverage Tax Policy: Lessons Learned from Tobacco” indicates that “as policymakers increase efforts to pass sugary beverage taxes, they can anticipate that manufacturers will emulate the strategies employed by tobacco companies in their attempts to counteract the impact of such taxes.” Pomeranz suggests that “policymakers should therefore consider two complementary laws—minimum price laws and prohibitions on coupons and discounting—to accomplish the intended price increase.”

Researchers at the University of Illinois, in a just-published study in the February issue of American Journal of Public Health, found that a 20 percent increase on the price of sugar-sweetened beverages would have an overall positive impact on the labor market.

The American Beverage Association has traditionally argued that manufacturers, distributors and small business owners, particularly grocers and convenience store proprietors, would suffer were soda taxes to be imposed, but the study says that’s not likely.

In recent years, proposals to tax those beverages fell short in California, Vermont, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New York and Rhode Island, Governing magazine reported. In Maine voters passed a soda tax of 42 cents per gallon in 2008 but repealed it two years later amid a major lobbying effort from the American Beverage Association. Voters in Washington state similarly reversed their legislature in 2010. As of the end of state legislative sessions in 2011, Governing reported, only four states had taxes specifically targeting sugary beverages, including Arkansas, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, according to the Tax Foundation.

In the study publ ished this month, researchers ran a simulation of the impact of 20-percent soda tax in Illinois and California—selected for regional differences—and found slight employment increases would occur, but the net effect would be close to nothing. They found that people choose to spend their money on other things, not to forego spending entirely, and that employment gains in other sectors of the economy far outweigh the job losses for soda makers, National Journal reported.

ished this month, researchers ran a simulation of the impact of 20-percent soda tax in Illinois and California—selected for regional differences—and found slight employment increases would occur, but the net effect would be close to nothing. They found that people choose to spend their money on other things, not to forego spending entirely, and that employment gains in other sectors of the economy far outweigh the job losses for soda makers, National Journal reported.

“We find there are losses in the beverage industry, but when you’re talking about the whole economy suffering job losses, you can’t just talk about your own industry,” Lisa Powell, health policy professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the study’s lead author, told National Journal. “Using job loss as a scare tactic for the economy overall is misleading.”

Public health advocates have warned of a link between added sugar and illnesses ranging from Type 2 diabetes and obesity to heart disease and osteoporosis. The caloric intake of sugary beverages increased dramatically from 1988 to the mid 2000s, though consumption has dropped across all age groups in recent years, Governing reported, with some citing the increased public attraction to teas and other beverages. Like Harp and Looney in Connecticut, some elected officials around the country have proposed raising taxes on sugary drinks in order to reduce consumption. The New Haven Register reported that Harp has pointed out that revenue from the cigarette tax has decreased, showing that the effectiveness of a tax in reducing consumption.

Pomeranz is a public health law and policy researcher focusing on marketing, labeling and youth access issues related to food and beverages, over-the-counter diet drugs, and dietary supplements, publishing on topics including discrimination, the First Amendment, public health preemption, and innovative regulatory strategies to address public health problems such as obesity. She is Assistant Professor at the Center for Obesity Research and Education in the Department of Public Health and at the College of Health Professionals and Social Work at Temple University, having served previously as Director of Legal Initiatives at the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity. She is currently the Policy Chair of the Health Law Section of the American Public Health Association and the official liaison between the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Public Health Association.

Lisa Powell is a Senior Research Scientist in the Institute for Health Research and Policy and Research Professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She has extensive experience as an applied micro-economist in the empirical analysis of the effects of public policy on a series of behavioral outcomes.

A 2011 study by the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity found that young people are being exposed to a massive amount of marketing for sugary drinks, such as full-calorie soda, sports drinks, energy drinks, and fruit drinks. The study, described as the most comprehensive and science-based assessment of sugary drink nutrition and marketing ever conducted, found that companies were marketing sugary drinks targeting young people, especially black and Hispanic youth.

“We are extremely proud of Dr. Ginsberg and congratulate him on this prestigious and well deserved award,” said Ellen Blaschinski, DPH’s Regulatory Services Branch Chief. “His expertise in toxic exposures and ability to consolidate vast amounts of science into easily digestible, useful information helps protect and inform Connecticut’s citizens.”

“We are extremely proud of Dr. Ginsberg and congratulate him on this prestigious and well deserved award,” said Ellen Blaschinski, DPH’s Regulatory Services Branch Chief. “His expertise in toxic exposures and ability to consolidate vast amounts of science into easily digestible, useful information helps protect and inform Connecticut’s citizens.”

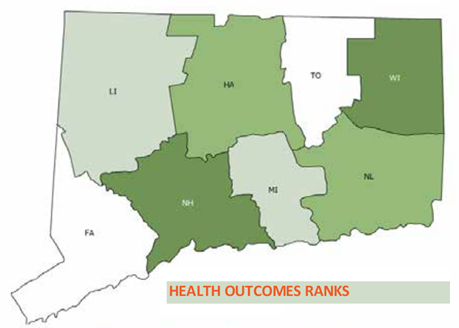

In health outcomes, Tolland County led the way, followed by 2)Fairfield County, 3)Middlesex County, 4)Litchfield County, 5)New London County, 6)Hartford County, 7)Windham County and 8)

In health outcomes, Tolland County led the way, followed by 2)Fairfield County, 3)Middlesex County, 4)Litchfield County, 5)New London County, 6)Hartford County, 7)Windham County and 8) New Haven County.

New Haven County.

an estimated

an estimated  as new spending from tax revenues. The other study says that tobacco taxes offer a how-to road map for policy makers.

as new spending from tax revenues. The other study says that tobacco taxes offer a how-to road map for policy makers. ished this month, researchers ran a simulation of the impact of 20-percent soda tax in Illinois and California—selected for regional differences—and found slight employment increases would occur, but the net effect would be close to nothing. They found that people choose to spend their money on other things, not to forego spending entirely, and that employment gains in other sectors of the economy far outweigh the job losses for soda makers, National Journal reported.

ished this month, researchers ran a simulation of the impact of 20-percent soda tax in Illinois and California—selected for regional differences—and found slight employment increases would occur, but the net effect would be close to nothing. They found that people choose to spend their money on other things, not to forego spending entirely, and that employment gains in other sectors of the economy far outweigh the job losses for soda makers, National Journal reported.

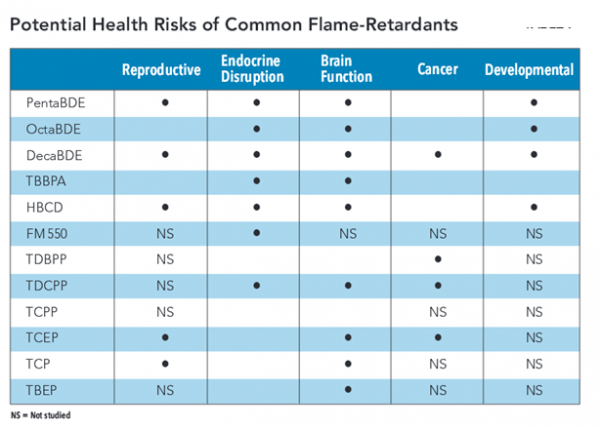

n, president of Environment and Human health, Inc. “It is time for flame-retardants to be removed from all low fire-risk situations and products. As well, a certification program should be established where manufacturers certify the absence of flame-retardants, just as organic food programs certify the absence of pesticides.”

n, president of Environment and Human health, Inc. “It is time for flame-retardants to be removed from all low fire-risk situations and products. As well, a certification program should be established where manufacturers certify the absence of flame-retardants, just as organic food programs certify the absence of pesticides.”

g human health from environmental harms. EHHI does not receive any funds from businesses or corporations. The organization’s mission is “to conduct research to identify environmental harms affecting human populations, promote public education concerning the relationships between the environment and human health, and promote policies in all sectors that ensure the protection of human and environmental health with fairness and timeliness.

g human health from environmental harms. EHHI does not receive any funds from businesses or corporations. The organization’s mission is “to conduct research to identify environmental harms affecting human populations, promote public education concerning the relationships between the environment and human health, and promote policies in all sectors that ensure the protection of human and environmental health with fairness and timeliness. ne-minute educational video

ne-minute educational video produced in the opening weeks of school, just prior to the mid-September entry deadline.

produced in the opening weeks of school, just prior to the mid-September entry deadline.

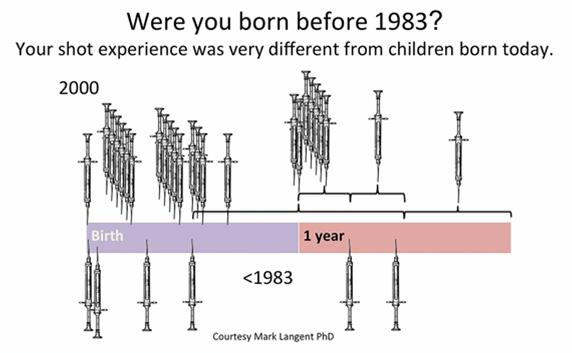

pecifically designed to remove pain from the injection.

pecifically designed to remove pain from the injection. ales. Baxter is one of Inc. Magazine’s Top Women in Tech to Watch, and is asked all over the world to educate physicians, nurses, Child Life specialists, and others about the importance of

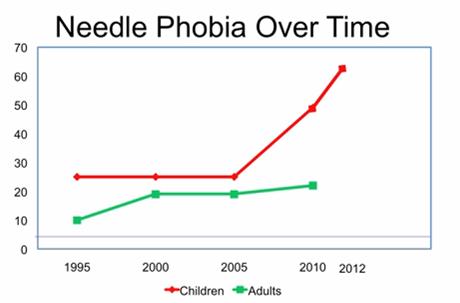

ales. Baxter is one of Inc. Magazine’s Top Women in Tech to Watch, and is asked all over the world to educate physicians, nurses, Child Life specialists, and others about the importance of  f needle-averse adults will have on their own health and the health care system.

f needle-averse adults will have on their own health and the health care system. away from the very remedies that can improve their individual health and the health of entire populations, warning that “by ignoring pain we’re endangering the future of health care.”

away from the very remedies that can improve their individual health and the health of entire populations, warning that “by ignoring pain we’re endangering the future of health care.”