by Jahana Hayes

My personal experiences are the greatest contributing factors to my becoming a teacher. These experiences shaped my views and continue to influence my teaching style. Being the first in my family to attend college helps me to fully appreciate the importance of education.

As a child everything I learned about school I learned at school. Teachers provided me with the support and encouragement to be a good student. My family provided for me; however education was not seen as a pathway to success. None of their experiences included higher education so they stressed the importance of hard work and industry. They told me to get a job with decent pay and benefits and work hard to support myself. This message was contradicted by the constant cycle of drugs, welfare and abuse that persisted in my family.

Teachers exposed me to a different world by letting me borrow books to read at home and sharing stories about their college experiences. They challenged me to dream bigger and imagine myself in a different set of circumstances. I was oblivious to opportunities that existed outside of the projects where I grew up, but my teachers vicariously ignited a passion in me. I was surrounded by abject poverty, drugs and violence, yet my teachers made me believe that I was college material.

Teachers exposed me to a different world by letting me borrow books to read at home and sharing stories about their college experiences. They challenged me to dream bigger and imagine myself in a different set of circumstances. I was oblivious to opportunities that existed outside of the projects where I grew up, but my teachers vicariously ignited a passion in me. I was surrounded by abject poverty, drugs and violence, yet my teachers made me believe that I was college material.

I can still remember the teachers who refused to accept the stereotypical views of inner city children and for them I am grateful. As a result, I entered this profession with a passion for the work that I do and an understanding that my work would extend beyond the classroom and into the world. I have a full understanding that many students come to school struggling to solve adult problems and teachers have to work through that before they can even begin to teach.

I became a teenage mother in high school and almost gave up on my dreams completely. However, my teachers showed me the many options that were still available if I continued my education. These positive experiences at school inspired me to become a teacher and that has always been my driving influence.

As a teacher, my own life is a constant reminder that students come from different circumstances and experiences. I have learned that teaching is a lifestyle that extends well beyond the contracted hours. I strive to meet students where they are, and not dwell on where they should be. I remember myself at various points in my journey and wonder how hopeless I must have seemed to the teachers who continued to work with me. They saw potential in me and did not give up even when it seemed like I would not graduate.

Working in an urban public school district with a widely diverse population, I see so many things that fall outside of traditional teaching responsibilities. It is those times when I am transformed into an advisor, counselor, confidant and protector. I also recognize that not all of my students have the same desire as I did to go to college. I remind them that this too is ok.

Students have to learn to be their best selves and pursue their own dreams even if higher education is not their best option. Many students are amazed that I don’t constantly push them into a college setting. I let them know that it is wholly acceptable to be an entrepreneur or a carpenter, hairdresser, plumber or whatever they desire.

One of the most critical issues affecting both education and society is the lack of empathy and understanding of others. If we show students that they are important, begin to engage them in dialogue, help them develop an appreciation for diversity and recognize that all people matter while they are still in school; many of the challenges we face in society will be improved.

As a teacher, I strive to facilitate learning in a way that engages students by connecting on a personal level and stimulating academic growth while simultaneously producing contentious and productive members of society. By serving their community students are able to demonstrate personal growth and model adult behaviors. This has become extremely personal to me because I feel that graduating students who demonstrate respect, responsibility, honesty and integrity is as critically important as mastering content and demonstrating proficiency.

As a child growing up in an urban poverty stricken environment, I only came in contact with one minority teacher. This contact greatly influenced the person I became. Most of my teachers lived outside the district and had experiences that were very different from mine. Many of my teachers were second or third generation educators and had always known they would be teachers. I saw little of myself in any of them.

As a child growing up in an urban poverty stricken environment, I only came in contact with one minority teacher. This contact greatly influenced the person I became. Most of my teachers lived outside the district and had experiences that were very different from mine. Many of my teachers were second or third generation educators and had always known they would be teachers. I saw little of myself in any of them.

I do not say this to imply that only minority educators would have a clearer understanding of my life, or that a minority teacher would have similar experiences; but to say that as a child I would have loved to see a teacher who looked like me and shared my cultural background.

In a recently published study in Economics of Education Review, it was shown that Black, white and Asian students benefit from being assigned to a teacher that looks like them. Their test scores go up in years when their teacher shares their ethnicity, compared to years when their teacher has a different ethnicity. It is very difficult to explain the feelings of isolation that come when you are in a school and the faculty is not reflective of your culture or heritage. As population demographics continue to shift, school districts must be intentional in their efforts to create a more diverse workforce.

As a teacher, I try to always be enthusiastic and express a sincere interest in my students’ academic success. I aim to inspire students to be more interested in the process than the product. I am constantly trying to challenge students to take a constructivist approach, ask questions, and in turn, apply their learning in different ways. My goal is for students to become self-directed, intrinsically motivated learners who are less concerned with grades and more concerned with gaining deeper knowledge and understanding.

While I have a passion for educating students, I am most proud of the influence I have beyond the classroom and I see this as my greatest contribution. Students are constantly coming to me for advice and direction. In my job I have been able to engage students in a variety of multi-faceted service projects. I never expected community service to be such a pronounced part of my work but the satisfaction that comes from watching students take ownership of their community is unmatched.

I believe that it doesn’t matter how bright a student is or where they rank in a class or what colleges they have been accepted to if they do nothing with their gift to improve the human condition. I try to teach students that we are all obligated to help others and improve society. Oftentimes people in the community ask me how I get so many young people to volunteer for community service and my answer is always the same, “I ask.”

_________________________________________

Connecticut’s 2016 Teacher of the Year, Jahana Hayes, teaches social studies at John F. Kennedy High School in Waterbury. In January, she was named one of four finalists by the Council of Chief State School Officers for National Teacher of the Year, which will be selected next month. This perspective is an excerpt of her 18-page National Teacher of the Year application. A native of Waterbury, she attended Naugatuck Valley Community College, Southern Connecticut State University, University of Saint Joseph and University of Bridgeport.

PERSPECTIVE commentaries by contributing writers appear each Sunday on Connecticut by the Numbers.

LAST WEEK: Suicide Prevention - Creating a Message of Hope for Young Adults

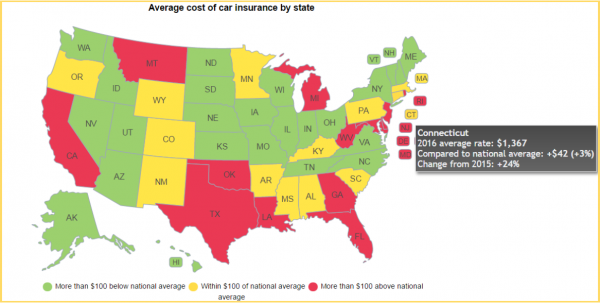

The national average for a full-coverage policy as featured in the Insure.com report came in at $1,325 this year – a slight increase from last year’s average of $1,311. Rates varied from a low of $808 a year in Maine to a budget-busting $2,738 in Michigan. Insurance rates in Michigan are more than double (107 percent) the national average.

The national average for a full-coverage policy as featured in the Insure.com report came in at $1,325 this year – a slight increase from last year’s average of $1,311. Rates varied from a low of $808 a year in Maine to a budget-busting $2,738 in Michigan. Insurance rates in Michigan are more than double (107 percent) the national average.

Teachers exposed me to a different world by letting me borrow books to read at home and sharing stories about their college experiences. They challenged me to dream bigger and imagine myself in a different set of circumstances. I was oblivious to opportunities that existed outside of the projects where I grew up, but my teachers vicariously ignited a passion in me. I was surrounded by abject poverty, drugs and violence, yet my teachers made me believe that I was college material.

Teachers exposed me to a different world by letting me borrow books to read at home and sharing stories about their college experiences. They challenged me to dream bigger and imagine myself in a different set of circumstances. I was oblivious to opportunities that existed outside of the projects where I grew up, but my teachers vicariously ignited a passion in me. I was surrounded by abject poverty, drugs and violence, yet my teachers made me believe that I was college material.

As a child growing up in an urban poverty stricken environment, I only came in contact with one minority teacher. This contact greatly influenced the person I became. Most of my teachers lived outside the district and had experiences that were very different from mine. Many of my teachers were second or third generation educators and had always known they would be teachers. I saw little of myself in any of them.

As a child growing up in an urban poverty stricken environment, I only came in contact with one minority teacher. This contact greatly influenced the person I became. Most of my teachers lived outside the district and had experiences that were very different from mine. Many of my teachers were second or third generation educators and had always known they would be teachers. I saw little of myself in any of them. ucation systems positively, the lowest percentages in the country, in a

ucation systems positively, the lowest percentages in the country, in a  State residents were asked “how would you rate the quality of public education provided in grades K-12” on a scale including excellent, good, fair and poor. The top 10 states after North Dakota, Minnesota and Nebraska are Iowa, New Hampshire and Massachusetts (80%), Wyoming (79%), South Dakota (78%) and Vermont and Virginia (75%).

State residents were asked “how would you rate the quality of public education provided in grades K-12” on a scale including excellent, good, fair and poor. The top 10 states after North Dakota, Minnesota and Nebraska are Iowa, New Hampshire and Massachusetts (80%), Wyoming (79%), South Dakota (78%) and Vermont and Virginia (75%).

The states with the largest Latino population are California, Texas, Florida, New York, Illinois, Arizona, New Jersey, Colorado, New Mexico, Georgia and North Carolina. With the smallest Latino populations are two New England states – Maine and Vermont – along with North and South Dakota and West Virginia. Another New England state, New Hampshire, is among the ten states with the smallest Latino population.

The states with the largest Latino population are California, Texas, Florida, New York, Illinois, Arizona, New Jersey, Colorado, New Mexico, Georgia and North Carolina. With the smallest Latino populations are two New England states – Maine and Vermont – along with North and South Dakota and West Virginia. Another New England state, New Hampshire, is among the ten states with the smallest Latino population.

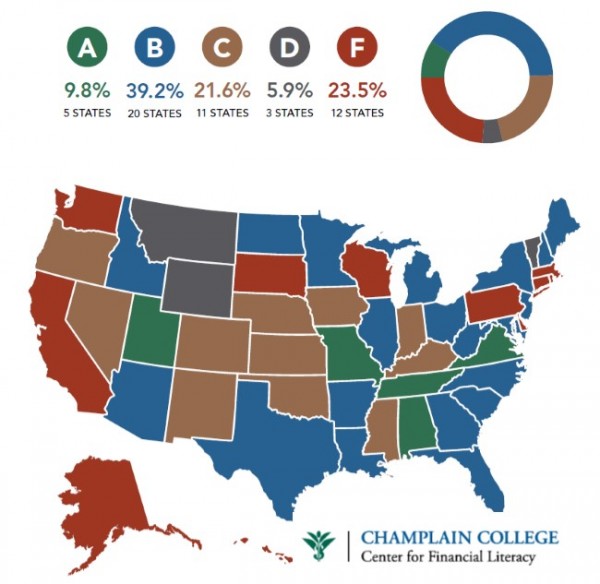

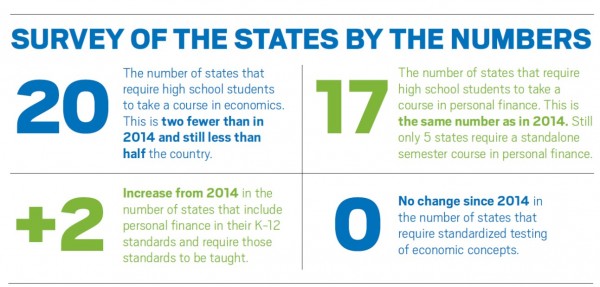

s a comprehensive look into the state of K-12 economic and financial education in the United States, collecting data from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The biennial Survey of the States serves as an important benchmark, revealing “both how far we’ve come and how far we still have to go.” This year the report concluded that nationally “the pace of change has slowed.”

s a comprehensive look into the state of K-12 economic and financial education in the United States, collecting data from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The biennial Survey of the States serves as an important benchmark, revealing “both how far we’ve come and how far we still have to go.” This year the report concluded that nationally “the pace of change has slowed.” nts accountable for learning objectives have the best chance of promoting the development of young people who are better financial managers and stewards of their credit—behaviors with which many, if not most, young people tend to struggle,” said J. Michael Collins of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Center for Financial Security. “Rigorous state standards can facilitate local schools to implement well-designed programs, which in turn expose students to concepts they otherwise would not learn.”

nts accountable for learning objectives have the best chance of promoting the development of young people who are better financial managers and stewards of their credit—behaviors with which many, if not most, young people tend to struggle,” said J. Michael Collins of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Center for Financial Security. “Rigorous state standards can facilitate local schools to implement well-designed programs, which in turn expose students to concepts they otherwise would not learn.”