Americans Moving Less Often, Changing Jobs Less Frequently - Divorce May Be Among Reasons Why, UConn Researcher Says

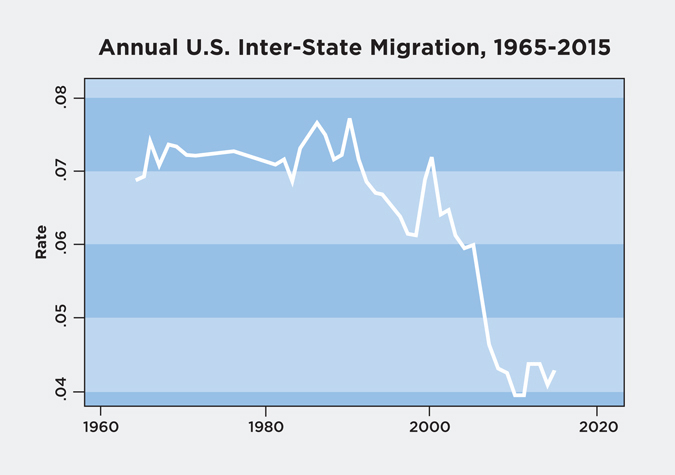

/Surprisingly, Americans are moving far less than they used to, only about half as much as they moved 50 years ago. And Americans aren’t moving or changing jobs with the frequency of decades past. Counter-intuitive, but true, according to the mounting data. In the early 1980s, about 17 percent of Americans changed their address each year. Now it’s less than 12 percent. Bigger moves, between different states, have dropped even faster, the Boston Globe reported this month.

“When Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, about one in 10 Americans changed occupations in a given year. As of 2012, it’s more like one in 24,” the Globe reported, citing data from a team of researchers at the Federal Reserve and the University of Notre Dame.

A researcher at the University of Connecticut has developed a theory regarding a key contributing factor to the diminishing moves and job changes.

“I’ve been banging my head against a wall for almost a decade, trying to figure out why migration rates are declining like this,” says Thomas Cooke, professor of geography in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

Cooke spent the spring of 2015 in the Department of Demography at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands on a Fulbright fellowship, where he worked on just this problem, UConn Today reported. His research findings give the first direct evidence for one major factor contributing to this trend: divorce and child custody.

“Changes in family complexity, like divorce and child custody, make a big difference for migration,” he told UConn Today. Cooke’s current work stemmed from the idea that in the 21st century, families are becoming increasingly complex. More women are working, people often live with elderly parents or grandparents, and step-children and cousins often live under the same roof.

Less moving is not good news for the economy, published reports have indicated.

Economists worry that the lower turnover is an indication of stagnation, not stability, the Los Angeles Times reported earlier this year. “Workers are staying put because there are fewer better jobs to move to, or they face other barriers that are keeping them locked in their current positions. And with declining job movement may come slower gains in overall employment, wages, productivity and, ultimately, economic growth,” the LA Times reported.

The Globe report suggests that “one big reason people jump between states and careers is because they’re lured away by the promise of higher pay and grander opportunities. The fact that fewer people are moving suggests fewer are getting those life-altering chances.”

The Times reports that experts also blame government policies for suppressing job creation and labor market mobility, whether through taxes or burdensome regulations. Government restrictions on who can work in which jobs have expanded greatly over time, academic economists Steven Davis and John Haltiwanger, who have written extensively on labor market flows, told the Times. Citing other research, they note that the share of workers required to have a government-issued license to do their jobs rose from less than 5 percent in the 1950s to 29 percent in 2008.

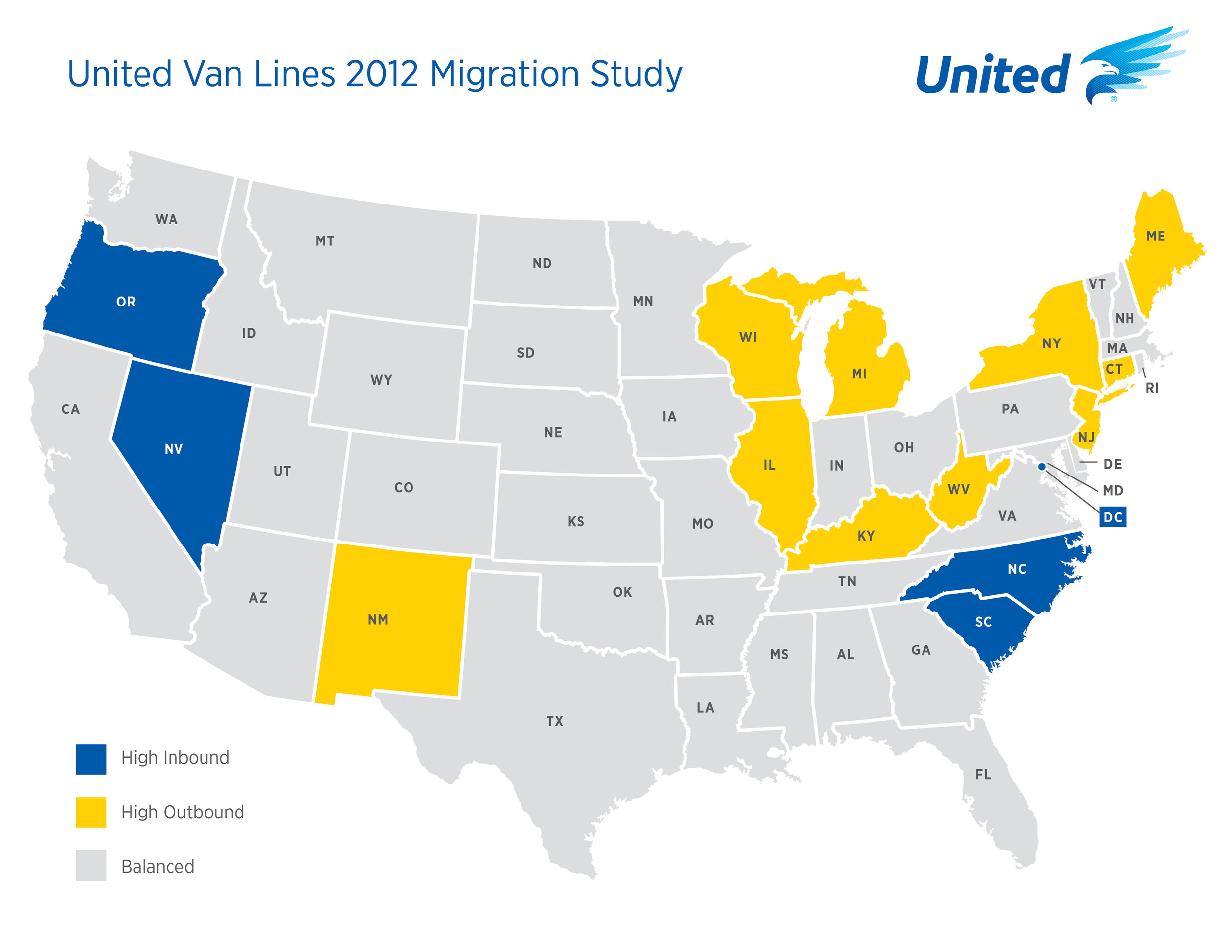

A New York Times report in May, citing data highlighted by the Brookings Institution, indicated that “Fluidity rates varied widely throughout the country, but the Brookings paper found that they declined in every state. Most of the largest drops occurred in the West: Oregon, Wyoming, Washington, Oregon, South Dakota, Montana, Idaho and Alaska were all in the bottom 10.

States with the most activity included North Carolina, South Carolina, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey and Illinois – but even these were not as fluid as they used to be, the paper reported.

There are broad adverse economic consequences to the lack of mobility, the Globe reports. “A recent study authored by two Harvard professors found that poor states are barely gaining any ground. Between 1880 and 1980, income differences among the states tended to shrink about 2 percent a year. This catch-up growth was only half as fast from 1990 and 2010. And if you focus on the few years just before the recession that began in 2008, there was virtually no convergence at all. Should this trend continue, the gap between rich and poor America may become a permanent feature of economic life,” the newspaper reported.

Cooke focused on child custody following divorce. His analysis confirmed that divorced people with children were even less likely to move than those without children. The findings support the idea that people’s lives are still linked, even if they divorce, Cooke explained. At the University of Connecticut Cooke has directed both the Urban Studies program and the Center for Population Research. His research focuses on the family dimension of internal migration, and the shifting concentration of poverty. In 2013 he earned the Research Excellence Award from the Population Specialty Group of the Association of American Geographers.

Cooke noted that the findings are the first direct evidence of divorce and child custody affecting migration in the U.S. Unlike the ’60s and ’70s, when state divorce proceedings usually awarded custody of children to the mother, joint custody is the norm today, he pointed out.

Combined with other factors affecting migration, such as the ease of telecommuting and the use of technology to communicate with loved ones far away, these divorce factors could spell a new era of rootedness, Cooke predicted.

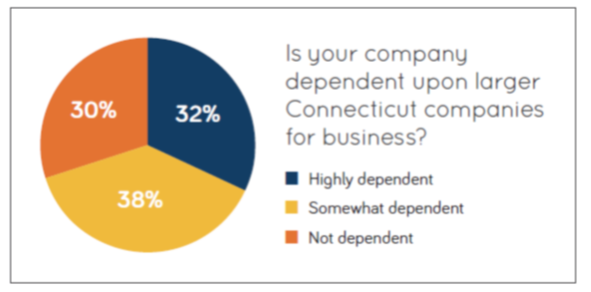

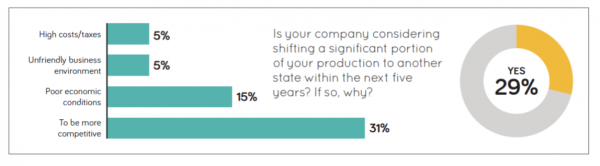

Whether perception drives reality or reality is drives perception, the opinions stated by business surveyed are less than encouraging, according to the report. Primary reasons cited for moving or expanding outside Connecticut are the state’s high costs (including taxes) and its “anti-competitive business environment,” reflecting an oft-stated CBIA viewpoint. More than three-quarters say Connecticut’s business climate is subpar compared with other states in the Northeast, and the nation.

Whether perception drives reality or reality is drives perception, the opinions stated by business surveyed are less than encouraging, according to the report. Primary reasons cited for moving or expanding outside Connecticut are the state’s high costs (including taxes) and its “anti-competitive business environment,” reflecting an oft-stated CBIA viewpoint. More than three-quarters say Connecticut’s business climate is subpar compared with other states in the Northeast, and the nation.