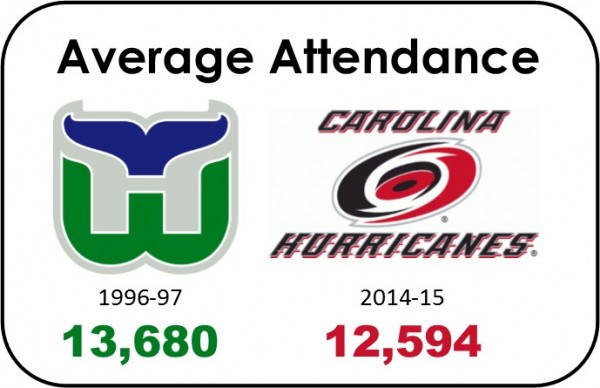

Whalers Departing Attendance, Carolina's Recent Attendance, Among NHL's Lowest (Hartford Higher)

/During the 2014-15 National Hockey League season, the teams with the lowest average home attendance were the Arizona (13,345), Carolina Hurricanes (12,594) and Florida Panthers (11,265).

So far in the current season, through 23 home games, the attendance for Hurricanes games has sunk even lower, averaging 11,390, lowest in the league. They are the only team in the league to draw less than 13,000 fans per game.

Fifteen years ago, during the 2000-01 season, the attendance numbers weren’t much better. Carolina had the league’s second lowest attendance, drawing an average of 13,355 per game for 41 home games. That ranked 29th in a 30-team league.

That was also only a handful of seasons after the teams’ move South, ending their 18-year history as the Whalers in Hartford, moving to Greensboro, North Carolina and becoming the Carolina Hurricanes for the start of the 1997-98 season.

In the 30-team league, during the past 15 years, Carolina has been among the league’s bottom-third in average attendance eight times, and the bottom-half every season but one. In 2006-07, the team ranked 15th in the league, their high-water mark. It was the season after the team won the league’s Stanley Cup. (The 2004–05 NHL season was not played due to a labor dispute.)

Those attendance number aren’t significantly different that the attendance levels when the team abruptly departed Hartford, nearly two decades ago. In early 1996, a 45-day “S ave the Whale” season-ticket drive resulted in 8,300 season tickets sold, about 3,000 more than the previous year. In the aftermath of the season ticket drive, and heading into the 1996-97 season, the Whalers management said they would remain in Hartford for two more years, in accordance with their lease.

ave the Whale” season-ticket drive resulted in 8,300 season tickets sold, about 3,000 more than the previous year. In the aftermath of the season ticket drive, and heading into the 1996-97 season, the Whalers management said they would remain in Hartford for two more years, in accordance with their lease.

In the Whalers' final season in Hartford, 1996-97, attendance at the Hartford Civic Center had grown to 87 percent of capacity, with an average attendance of 13,680 per game. Published reports suggest that the average attendance was, in reality, higher than 14,000 per game by 1996-97, but Whalers ownership did not count the skyboxes and coliseum club seating because the revenue streams went to the state, rather than the team. Attendance increased for four consecutive years b efore management moved the team from Hartford. (To 10,407 in 1993-94, 11,835 in 1994-95, 11,983 in 1995-96 and 13,680 in 1996-97.)

efore management moved the team from Hartford. (To 10,407 in 1993-94, 11,835 in 1994-95, 11,983 in 1995-96 and 13,680 in 1996-97.)

During the team’s tenure in Hartford, average attendance exceeded 14,000 twice – in 1987-88 and 1986-87, when the team ranked 13th in the league in attendance in both seasons.

Last season’s top attendance averages were in Chicago (21,769), Montreal (21.286), Detroit (20,027), Philadelphia (19,270), Washington (19.099), Calgary (19,097), Toronto (19.062), Minnesota (190230 Tampa Bay (188230 and Vancouver (18,710). The New York Rangers drew an average of 18,006, ranking 17th in the league in average attendance.

Florida’s attendance last year was a league-low 11,265; Arizona was 13,345 per game. The previous season, the New York Islanders, Columbus Blue Jackets, Dallas Stars, Florida Panthers and Arizona Coyotes all drew less than 15,000 fans to home games across the season. So far this season, with about half the home games played, five teams continue average 14,000 fans per game or less.

On March 26, 1997, Connecticut Gov. John G. Rowland and Whalers owner Peter Karmanos Jr., who had purchased the team in 1994, announced that the Whalers would leave Hartford after the season because they remain far apart on several issues, with the main sticking points linked to construction of a new arena. The team agreed to pay a $20.5 million penalty to leave at the end of the season, a year before its commitment was to expire.

The final Whalers game in Hartford was on April 13. Less than a month later, the Carolina Hurricanes were born, beginning play that fall in Greensboro while a new facility was built in Raleigh. Efforts to bring the NHL back to Hartford since that day have been unsuccessful.

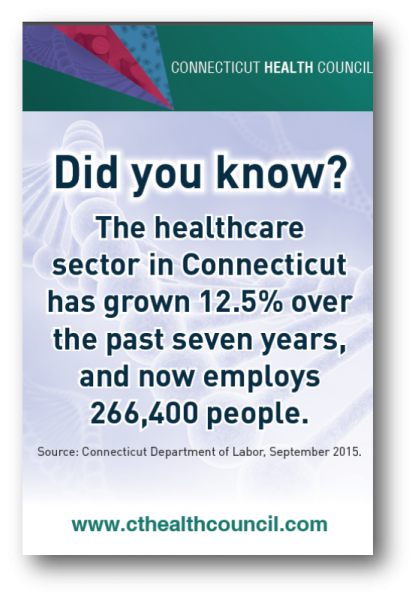

In addition, the marketing campaign also highlights that thee of the top 10 fastest growing companies headquartered in Connecticut in 2014 were healthcare related companies, and that Connecticut’s healthcare sector has the fifth highest number of sole proprietorships of any sector in the state, with the seventh highest revenues. Connecticut’s “unique base of health sector assets” include health insurance companies, hospitals, medical schools, research capacity, and specialty practices, according to the organization’s website.

In addition, the marketing campaign also highlights that thee of the top 10 fastest growing companies headquartered in Connecticut in 2014 were healthcare related companies, and that Connecticut’s healthcare sector has the fifth highest number of sole proprietorships of any sector in the state, with the seventh highest revenues. Connecticut’s “unique base of health sector assets” include health insurance companies, hospitals, medical schools, research capacity, and specialty practices, according to the organization’s website.

The Council's primary activity is to host programs focused on health sector topics that feature speakers of regional, national and international renown, the website points out. The Council also provides “a forum for a robust network of experts, professionals and other parties interested in promoting Connecticut as a center of health excellence and the health sector as a primary driver of economic and employment growth in our State.”

The Council's primary activity is to host programs focused on health sector topics that feature speakers of regional, national and international renown, the website points out. The Council also provides “a forum for a robust network of experts, professionals and other parties interested in promoting Connecticut as a center of health excellence and the health sector as a primary driver of economic and employment growth in our State.”

Since entering the Connecticut market in the summer of 2014, the company has been aggressively growing its customer base in a competitive market while working diligently to grow and expand its network of doctors. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care announced recently that its Connecticut membership has grown to more than 24,000, exceeding expectations for 2015. It now serves more than 800 Connecticut businesses. Twenty-nine of the state’s 30 hospitals are now in-network.

Since entering the Connecticut market in the summer of 2014, the company has been aggressively growing its customer base in a competitive market while working diligently to grow and expand its network of doctors. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care announced recently that its Connecticut membership has grown to more than 24,000, exceeding expectations for 2015. It now serves more than 800 Connecticut businesses. Twenty-nine of the state’s 30 hospitals are now in-network. With more than 500 business leaders in attendance at an annual Economic Summit & Outlook last week, brought together by the Connecticut Business and Industry Association and MetroHartford Alliance, Schmitt spent some time touting a new model launched in the state of New Hampshire that he believes may be a glimpse into the direction the industry is moving. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care’s footprint in New England now covers “where 90 percent of New Englanders live,” in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maine and New Hampshire.

With more than 500 business leaders in attendance at an annual Economic Summit & Outlook last week, brought together by the Connecticut Business and Industry Association and MetroHartford Alliance, Schmitt spent some time touting a new model launched in the state of New Hampshire that he believes may be a glimpse into the direction the industry is moving. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care’s footprint in New England now covers “where 90 percent of New Englanders live,” in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maine and New Hampshire.

Launched

Launched

MassChallenge, an independent nonprofit organization, envisions “a creative and inspired society in which everyone recognizes that they can define their future, and is empowered to maximize their impact.” They note that “novice entrepreneurs require advice, resources and funding to bring their ideas to fruition. Currently there is a gap between the resources these entrepreneurs need and the ability of the entrepreneurial ecosystem to provide them.” To bridge that gap, the organization’s primary activities include running an annual global accelerator program and startup competition, documenting and organizing key resources, and organizing training and networking events. They “connect entrepreneurs with the resources they need to launch and succeed immediately.”

MassChallenge, an independent nonprofit organization, envisions “a creative and inspired society in which everyone recognizes that they can define their future, and is empowered to maximize their impact.” They note that “novice entrepreneurs require advice, resources and funding to bring their ideas to fruition. Currently there is a gap between the resources these entrepreneurs need and the ability of the entrepreneurial ecosystem to provide them.” To bridge that gap, the organization’s primary activities include running an annual global accelerator program and startup competition, documenting and organizing key resources, and organizing training and networking events. They “connect entrepreneurs with the resources they need to launch and succeed immediately.”

This summer, Shemitz was among those appointed to serve on the state’s Commission on Economic Competitiveness, created by the legislature amidst concerns in the state’s business community about the perceived lack of competitiveness. The Commission is considering steps to improve Connecticut’s employment and business climate including measures to support workforce development and family and economic security. Recommendations are anticipated for legislative action next year.

This summer, Shemitz was among those appointed to serve on the state’s Commission on Economic Competitiveness, created by the legislature amidst concerns in the state’s business community about the perceived lack of competitiveness. The Commission is considering steps to improve Connecticut’s employment and business climate including measures to support workforce development and family and economic security. Recommendations are anticipated for legislative action next year.